Bob and Jack discuss the performance of White House Counsel David Warrington and examine last week’s lethal strike on alleged Venezuelan terrorists—including its possible implications for domestic presidential military strikes.

This is an edited transcript of an episode of “Executive Functions Chat.” You can listen to the full conversation by following or subscribing to the show on Substack, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Jack Goldsmith: Good morning, Bob.

Bob Bauer: Good morning, Jack.

There’s been so much in the news since we last chatted, which was quite a while ago, actually. Today, we’re going to focus on some topics that we know a little bit about. We’re going to discuss two stories from last week about Trump administration lawyering: the long New York Times profile on your successor in the White House Counsel’s Office, David Warrington, and the administration’s lethal strike on a speedboat in the southern Caribbean that allegedly contained members of the designated Venezuela terrorist organization Tren de Aragua, allegedly transporting drugs to the United States.

These connect insofar as they involve executive-branch legal decision-making. Why don’t you begin by summarizing and commenting on the New York Times story about Warrington?

A number of things struck me about the story about Warrington. Of course, it was published against the background of a lot of debate about the role of the White House counsel—the extent to which the White House counsel has supplanted the Department of Justice (DOJ) as the principal channel for legal advice to the president. What that means if presidents pick White House counsels who are particularly friendly to them, have personal or political backgrounds with them, and can be expected to be, if you will, loyal and pliant.

Some of that debate has been, in this administration, overtaken by events, because once there was a thought that presidents would nominate somebody relatively uncontroversial—down the middle, if you will—as attorney general, and then have a White House counsel who is much more in that world of friendliness and political background. Now, of course, this particular president has chosen from his own personal legal team the senior officials in the DOJ. So that particular concern about the White House counsel may have been overtaken by events. But it’s still a very powerful legal office right there in the West Wing, one floor above the Oval Office, and probably the last word on any critical legal question that the president has to address.

What I found striking, in that article, was that David Warrington gave the interview to the New York Times, understanding perfectly well that that’s a locus of criticism of the president’s legal stances. He said two things that were somewhat in tension. One was that he didn’t feel he should be giving his personal views: He gave the advice he gave, and unless asked, he didn’t say more. But later on, he said he gave the advice that he gave and there was some inclination or some suggestion that he spoke his mind… it wasn’t entirely clear.

I have to say, in an administration like this, I’m skeptical about a White House counsel who says, “I’ll keep my thoughts to myself; I’ll just give him my reading of the law. And if I have any concerns about the direction we’re going, I’m just not going to express them.” I have real concerns about that, in any presidency, but particularly in this one. Second, he said his role was to advise with a view toward finding “defensible” positions for the administration to take—e.g., strategies courts have criticized for deporting and trying to avoid court jurisdiction. He was looking for defensible positions and to reduce risk.

That raises two questions: What is a defensible position? What’s the standard for determining what a defensible position is? And secondly, what does it mean to reduce risk—what kind of risk are you talking about? The risk that the courts will overturn it? The risk that it will provoke congressional opposition or complaint, particularly from your own side of the aisle? It wasn’t clear how he was, as a professional, defining the way he would approach his job in this very challenging administration where the president has displayed so little regard for the rule of law.

I want to press you on a bunch of those points. My reaction to the story was that it was kind of anodyne, actually. I thought a profile of Warrington would show him in the tank for the president, and it wasn’t quite that. Can you briefly explain, to the extent that there is a traditional explanation, the traditional role of the White House counsel as opposed to the traditional role of the attorney general?

The White House counsel is a member of the president’s senior staff—end of story. No authority to bind agencies with legal interpretations; a counselor picked by the president, not subject to Senate confirmation. The attorney general of the United States is the second most-senior (to the president) law enforcement officer in the constitutional system, nominated to the Congress, to the Senate, confirmed or rejected by the Senate. And there's been a view, particularly after the Nixon debacle in the Watergate era, that an attorney general has to stand for a department that is like any other department. It's not independent of the president in a formal sense, certainly needs to be attentive to the president's policy priorities. But at the same time, in law enforcement activities in particular, has to avoid any suggestion of political favoritism or impartiality and therefore establishes independence in that sense.

There are no criteria like that for the White House counsel. There's no criteria at all prescribed anywhere for the White House counsel. It's really a position that's governed by expectations and by norms—that as influential as a White House counsel can be with such close proximity to the president, the White House counsel will be guided by a concern for representing the presidency as an institution and not merely operating, which he or she shouldn't, as a personal or political lawyer to the president.

But isn't it also true (I think we wrote in our book together) that the White House counsel is at the heart of political decision-making inside the White House? Is it fair to say that in a normal administration, the White House counsel is more of a political/legal counselor as opposed to providing the account of the law that should guide the executive branch? Is that—can you just get at that a little bit? Because that'll lead me to my questions about how Warrington was presented.

There is always the possibility that that's how the White House counsel sees his or her job as a lawyer—member, loyal member—of the senior legal team. In my time, and I know there are other White House counsels who have shared this view, I thought it was I thought it was very important for the office to distinguish itself from other senior staff members and retain its credibility as legal advisers by not seeming to be full-throated members of the president's political or communications team. The risk of the White House counsel being both a political adviser and a legal adviser is that other members of the senior staff—or the president himself—might wonder, when getting a piece of advice: Is this advice shaped by the law, or is it shaped by the political or communications judgment of the White House counsel? And for a White House counsel, in my view, to have credibility, there has to be no question that their advice is shaped by the law.

Now, if they have some view about the political consequences of taking a particular legal position—Congress will object, the press will rise up in fury, allied ideological groups will be unhappy… Then the White House counsel could bring that into the conversation if somebody else doesn't, but can say—and should say, by the way—separately and apart from the legal advice just given, that these other political consequences could follow. But I think it's very important for the White House counsel's office to be a legal operation and not an adjunct of the political and policy operation of the president.

Right. Now, I didn’t mean to suggest that it should be an adjunct, and he didn’t even present himself as one. He presented himself as providing legal advice about legal risk. One of the interesting things about the story is that it described a White House counsel’s office that was more law-heavy, doing more DOJ-type legal analysis. I think that’s what I read between the lines of the story.

And that he, in some sense, had a more enhanced—arguably more enhanced—legal role than the average White House counsel, because they have not wanted to go to OLC and other elements of DOJ.

Can I just mention one think quickly, Jack? He referred to it as more of a litigation shop than any of his predecessors.

Right. And so what about that? I mean, you asked the question—he said he was assessing risk. My understanding of the White House counsel's office has been that the law is vetted and presented, including various possible interpretations of the law. Then the president faces legal risk and political risk. And I think it’s important to mention that the president of the United States under Article II is the legal decider for the executive branch.

So ultimately, the president—whether a lawyer or not—gets to decide. Part of what I understood the White House counsel to be doing was assessing and advising the president about all of these risks. Is that right or wrong?

No, that’s right. It goes to the point I made earlier about distinguishing legal risk from other kinds of risks like political risk, and being very clear. The White House counsel should be explicit when there is a political risk in addition to a clearly presented legal risk. A legal risk is: you’re breaking the law. You are breaking the law. You are doing something that, as the president takes care that the law is faithfully executed in accordance with constitutional responsibilities, you shouldn’t do.

Then there’s also legal risk in the sense that a president could be sued. The administration could be sued over an action and could find that action successfully challenged in court. There’s also legal risk of a constitutional dimension if they take an action that could lead to the institution of impeachment proceedings. Those are all legal risks.

Other risks are political uproar, bad reaction among allied ideological groups, or loss of support among independents as measured by constant White House polling. Those kinds of risks exist as well. But first and foremost, the question has to be: Are you taking the risk of violating the law, of exceeding legal and constitutional boundaries in the decision you’ve taken?

And it just wasn’t clear to me—and granted, Warrington in the article doesn’t go on at great length about it—what it meant when he said, “We want to reduce the risk.” Because if you look at precedent—take the executive orders that involve law firms, for example—those are clearly unlawful. Was the judgment there: “Yes, you’re taking the risk of breaking the law, the risk of being reversed by a court… But those are acceptable risks because nothing else is going to happen to you, and it’s going to have an interim effect on the legal community. So your desire to spook the legal community will be successful.” To me, that wouldn’t be responsible lawyering.

Why? And let me give you another example to flesh it out—and I tend to agree with you, I just want to flesh out the point. They gave the example of the deportations before Judge Boasberg. Very early in the administration, it looked like DOJ was defying Judge Boasberg and deporting certain Venezuelans outside the United States. There was a question whether Boasberg ordered the planes to turn around at some point, and whether they had to comply with that.

And Warrington and the deputy attorney general came up with the theory that they had a good legal argument: if the deportees were outside the United States, then they were outside the scope of the judge’s order, and the planes didn’t have to turn around.

I thought that argument was a stretch at the time, but it ultimately prevailed—not necessarily because it was the right call on the law, but because when Judge Boasberg held a contempt proceeding, the D.C. Circuit, by a 2–1 vote, held that contempt was not appropriate for that ostensible disobedience of the order. So the administration prevailed on that, based on what sounds like the Warrington legal theory. How do you assess that? Is that an okay role for the White House counsel to be playing?

There’ll be a debate about that. I’m sure. I’m very troubled by what I infer from the article’s reference to a “defensible position.” Again, this was the reporter’s characterization of their conclusion. To be fair, I wasn’t in the room and didn’t hear how strong or weak they thought that legal argument was.

But when I was in the White House, I would hear various lawyers speak about different standards for determining legal risk that ranged from whether a legal argument was “plausible” to even “available”—meaning really, really weak, but technically could be made. What troubles me about the word “defensible” is that it could mean, “We can put it on paper and maybe avoid sanctions,” but in truth, it’s a terrible legal argument with serious implications for the presidency.

That’s the point I want to stress. The White House counsel—though appointed by and serving a particular president—represents the institution of the presidency, not President Trump in his personal or political capacity. Therefore, it is extremely important in these conversations that the White House counsel is very clear about what constitutes a legitimate, strong, good-faith legal argument, and what is one the president can simply get away with making.

So ultimately, for me, this is a very tricky question because it’s the president’s call. My baseline assumption was that Warrington would take the stance of, “Whatever you want to do, sir, we can do.” But that’s not how the story presented him. The story showed him offering legal views, with the president interested in various perspectives, and then the president deciding. In some sense, that’s a normal process—although we know here that President Trump holds a maximal view of executive power and that this administration is in many contexts indifferent to law.

So what do you do as White House counsel, other than not take the job, when there is a president exercising his authority to interpret the law for the executive branch with such an expansive view of executive power as to not be constrained at all? How does one even think about that as White House counsel?

Granted, it’s a very difficult question when someone decides to become the White House counsel to a President whose views on executive authority and on the law are as well known as Donald Trump’s were when David Warrington took the job. But I think there has to be some suggestion—and again, the story was not complete about this, though it may be taking place—that the White House counsel is digging in and making an issue of legal compliance within the administration.

Defensible positions, and also the suggestion that he gives the answer he gives but doesn’t express “personal views,” alarms me. It suggests a tilt toward: “Well, whatever you say—listen, this is completely inconsistent with the law, but I’ll come up with the best argument I can to protect it or cover for it.” That’s not the way you want the best White House counsels to perform.

And again, Warrington gave an interview, but he didn’t say much. The people in the background who provided additional reporting for Charlie Savage in the New York Times didn’t provide much detail either. But given the kind of administration this is, you would have liked to see a little more robust defense of the professional and ethical responsibilities of the White House counsel.

OK, let’s move on to the speedboat—the legal force against the speedboat. I’ll quickly run through the relevant background, because I think it’s important. This was a boat allegedly containing members of Tren de Aragua, which the Trump administration designated as a terrorist organization, and whose alleged members it is also trying to deport under the Alien Enemies Act in the United States.

There’s a longstanding conflict between the United States and the Maduro regime in Venezuela. In Trump’s first term, President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela was indicted on drug trafficking charges as a cartel head, back in 2020. As I said, Tren de Aragua was deemed a terrorist organization, and the president determined that they were undertaking hostile actions and conducting irregular warfare against the U.S. through unlawful immigration and narcotics trafficking.

In July, according to the New York Times, the president signed a directive to the Pentagon authorizing military force against Latin American drug cartels deemed terrorist organizations. That would include this one, and presumably that was the directive relied on here.

There’s been a big U.S. military buildup in the Southern Caribbean. And then finally, the strike took place on September 3.

The president sent a War Powers Resolution letter to Congress and essentially said, “I can do this under my Article II powers.” He did not rely on any statutory authorization from Congress. Instead, he cited his responsibilities to protect Americans and U.S. interests abroad, and to further U.S. national security and foreign policy interests.

He also hinted in the letter that other nations were “unwilling and unable” to stop this threat—an allusion to a standard in international law. So that’s the basic legal architecture we know here.

Domestically, the question is whether the president is authorized under Article II; internationally, whether the strike is consistent with international law or stretches it. I would say the international-law argument is a large stretch.

From one perspective, this represents a new assertion of presidential power: And the key thing is using force against terrorist-designated organizations that are part of a nation or group not otherwise in armed conflict with the United States, though the president claimed they were engaged in irregular warfare. It’s extending it. We extended presidential power to use force against terrorists beginning after 9/11, and that expanded in various ways. But this is another expansion—under Article II power.

Now, I will say that while it’s an expansion, it’s not necessarily out of line with the evolution of the president’s Article II power. This is how presidential power expands: they build on precedents, point to those precedents, pick up on language in them, and extend it to a new factual situation. That’s essentially what’s happened here.

The OLC opinions on Article II power are so open-ended and permissive that it’s not a crazy interpretation to say the president has this authority under Article II. It is, however, a fateful step for a president to use Article II power to go after drug criminals deemed terrorist organizations. That’s the situation as I see it. On the international-law side, I don’t think any serious lawyer would say this constitutes self-defense under customary international law or the U.N. Charter, because we’re not in an armed conflict. There’s just not the adequate level of violence between either this group or Venezuela and the United States.

The last thing I’ll say, however, is that it’s clear the United States is building up a military presence vis-à-vis Venezuela. It’s clear they are trying to raise the military stakes and bring this into the level of warfare under international and domestic law. That strike was the first exemplar of that.

On that argument, the president has extraordinary unilateral power to do it. It’s one of those facts of life: the president controls the military and can invite or initiate hostilities with other nations. He gets to determine and characterize the conflict.

And the point I wanted to make is, as others have, this has relevance to the Alien Enemies Act argument in the United States about whether the president has properly invoked the Alien Enemies Act. The more this conflict with Tren de Aragua looks like real war—looks like lawful warfare—the stronger the president’s arguments are under the Alien Enemies Act to deport.

So that’s my take on it. Do you have any reactions?

I have a couple of questions. First, I want to bring up one legal question. In the president’s War Powers letter, he says that he assessed that Tren de Aragua was a foreign terrorist organization. He acknowledged that it was because it is, and that it was engaged in drug trafficking.

What is the legal significance, for purposes of the boat attack, of their having been designated a foreign terrorist organization?

The designation as a foreign terrorist organization by itself does not automatically trigger the president’s Article II powers. It has to be tied to a national interest. And again, we’re moving in a direction that DOJ opinions have never quite gone to. But the national interests identified in OLC opinions are so expansive that it’s not hard to frame this as a national interest sufficient to warrant the use of force under domestic law.

But the designation as a terrorist organization by itself does not trigger Article II powers to use force. It takes extra steps, though I’m not sure how hard it would be to meet those steps here.

That brings me to another question, and then one about consequences or the broader framework in which presidential power is repeatedly expanded in this fashion, step by step. If the president can say, for example, that there are dangerous forces at work—conceivably fed by foreign enemies, making payments for it, encouraging them, whatever—but they’re active in our major cities, and he may be required to deploy forces to those cities, what is it in this claim of Article II authority that would prevent him from authorizing an attack on the headquarters of a domestic organization he believes may be encouraged by foreign sources, but is engaging in the kind of activity that, most recently in a meme he posted, justifies intervention by the Department of War in the city of Chicago, for example? What is the limiting principle in this claim of Article II authority to protect the national interest in this way?

Yeah. So you’re asking whether he could use this justification to use force inside the United States.

That’s correct.

So—wow. OK, that’s too hard a question for me to answer. I’ll just say a few things. This came up during the Bush administration with José Padilla, when he was captured inside the United States and deemed to fall under the post-9/11 Authorization for Use of Military Force. The question arose whether the president could have used military forces as Padilla was coming off the plane, rather than simply capturing him.

Frankly, there was a lot of debate about that. And it’s actually a much harder question than you would think. I mean, I think the answer has to almost certainly be no—that the president would need to use police forces and other domestic authorities, and that his essentially self-defined Article II powers to go after these groups couldn’t be used inside the United States.

But it was always a hard argument to explain why, if you really accept the premise that we’re in a conflict with this group and that group happens to be inside the U.S. The parallel, of course, is the Civil War—and obviously that’s not a close parallel in terms of scale or what was going on. But if the president’s war powers are triggered, why can’t he use it? Again, I would—and could—write the memo saying it was unlawful, but you could also write the memo the other way, as horrible as that sounds, arguing that the president could be empowered to use military force domestically. That’s my shorthand answer. It’s more complicated than that, and some people will disagree with me, but that’s the way I see it.

But domestically, to be clear—and I just have one wrap-up question here—what I’m focusing on is his determination that the terrorist activity is in no way authorized under any of the authorizations to use military force dating back to the Iraq invasion. This would be a current threat to U.S. national security by a domestic group, perhaps supported by foreign funding or encouragement, but conducting what he called, in the case of Tren de Aragua, “irregular warfare” within the United States.

And you’re suggesting there may be administration lawyers who would be open to that argument.

I mean, I can imagine them making the argument, yes. This is one of those issues—like so many raised by the Trump administration—where theoretical arguments take you in a certain direction, and people say, “Well, no one would ever do that, so we don’t need to worry about that issue”

And, you know, there are very powerful arguments that the president couldn’t do that. But it’s not as though there’s a Supreme Court decision forbidding it. And it’s not as though you couldn’t cobble together an argument to justify it. So it’s a very scary prospect: the president using the same rationale, against the same so-called terrorists, inside the United States. Why not?

Again, the law probably requires the president to use law-enforcement authorities domestically, and not use his Article II military powers. But you could make the argument the other way.

What I want to emphasize is that we are taking an extreme argument used in territorial waters outside the United States and asking how that extreme argument would play out in the domestic realm. And it’s already on weak ground outside the United States. But here’s the issue: who is going to stop him from doing it? The courts are not going to get involved in the use of force outside the United States. Congress never has—and Congress is the institution that is supposed to police and control this, but it’s out of commission.

The courts would definitely get involved if military force were used inside the United States, whether they wanted to or not, and whether or not they treated it as a political question. There would be efforts at judicial accountability in that scenario.

But the idea that courts are going to save us from this—as I’ve been emphasizing recently—is just not the right focus. It’s really a question of what the politics will hold, and how extreme they want to be in using these authorities. And I guess my concern is that they’ve been using these military authorities in a whole variety of contexts, kind of at a relatively low level inside the United States so far, with the National Guard deployments in various ways.

But slowly and surely, these are building up into what are going to be more powerful arguments. They have more powerful authorities under the Insurrection Act that they haven't yet used. I'm not talking about your hypothetical now, but for quelling domestic violence and the like. And I think that the administration thinks that these arguments are good for it. I think that they think that the American people are on board—or at least their supporters are on board, for really going hard after criminals, for really going hard after drug dealers, for really going hard after illegal immigrants, for really going hard after terrorists.

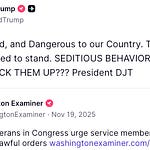

The Vice President’s comment about the use of force against the boat, when it was claimed that it was murder and possibly a war crime, was that he “didn’t give a [bleep].” This was basically the vice president of the United States expressing utter indifference to the law and, again, kind of glorifying the use of military force in this controversial context. So the worry is that they're building up confidence in the use of these military authorities domestically. And I don't know. I don't know how far it will go. I don't know where the politics will stop it.

Yes, and so let me just very quickly respond to that in a kind of wrapping-up point. One is that I don’t have the Vance comment in front of me, but there’s nothing in what he said about the ‘highest and best use of the military’ that suggests it would be confined to the same threats he sees operating inside the United States—number one.

Number two, what you described goes back to the Warrington article. The White House counsel, making an argument for my hypothetical, for the administration’s actions in my hypothetical, could characterize it as a “defensible position.” If “defensible” is stretched that far—if an argument can simply be made—then the administration can claim a legal justification for it

Number two, what you described is something that, going back to the Warrington article, the White House counsel, an argument for my hypothetical, for the administration's actions in my hypothetical, what was described in the Warrington article as a defensible position. If defensible is stretched that far, an argument could be made, then the administration can claim a legal justification for it. And that brings me to my wrap-up question. When we use the term stretch, we suggest that it’s still within the realm of reasonable argument, because something’s been done before that could be pulled a little bit in that direction—so it’s “kind of a stretch.”

But at the end of the day, where do the stretches end? If every step leads to the next—step A leads to step B, which is characterized as a stretch, but step B is taken, then step C is taken, which is characterized as a stretch on step B—where does it end?

It ends—and I don’t mean this to be glib—it ends only when the American people say it ends. And by that, I mean Congress through political pressure, or the people through elections or through other means. Because the president will, it seems, do what he thinks he can get away with politically and/or legally. o I don’t know where it ends, but to the extent that the administration perceives it gains an advantage, I think it will continue moving slowly along these lines, testing how far it can go.

I don’t disagree, but I want to return to the responsibility of lawyers within the government. At the end of the day, no, they don’t have the final say—and you can always pick the lawyer you think will give you the advice you need.

There are lawyers out there prepared to sell—whether for free or for a dear price—the advice that their clients want. But you would hope, and expect, that the legal profession inside the government would put up a fight in these circumstances.

But I don’t disagree with you. At the end of the day—and here’s my final expression of naïveté—I don’t disagree that the ultimate answer lies in the public standing up, in the Congress standing up, and in the electorate standing up for a vision of the rule of law in this country that does not permit the hypothetical to become a reality.

I’ll make a wrap-up point. The American people are, for better or worse—though I think worse—kind of indifferent to the use of military force abroad. When the casualties are non-U.S. citizens and Americans are disengaged, we’ve seen over the last 20 years that as war has grown quieter in terms of American casualties, the public cares less and less.

But I do believe that at some point the tolerance for the militarization of the domestic sphere will break down. I think it won’t be tolerated in some quarters of the Republican Party, as weak and deferential as it is to the president. So I do think there are special political dangers here. We’ve talked about this: the importance of reforming the Insurrection Act, and why that reform might have more bite than the analogous War Powers Resolution—precisely because of the political dangers of militarizing the domestic sphere. I don’t want to be naïve about that, but I think it is politically more challenging for a president.

The last thing I’ll say is about the role of lawyers. This is an administration where everybody knows what President Trump’s view of his legal authority is, and how he wants to be listened to. There are executive orders and memoranda to that effect. There are interim threats throughout the administration that if you don’t follow the president, you’re out.

So to the extent that people are asked to give candid legal views, it’s only with the understanding that “we’re going to make the decision,” as is their prerogative in the White House. I just don’t think there’s a culture in this administration—or a context, or even permissiveness—for the kind of candid lawyerly pushback you’re contemplating. There’s always been a tension on this, but here I think they’ve successfully organized themselves to prevent that kind of legal advice.

I don't disagree.

It's a good place to stop. Thanks, Bob.

Thank you.