In this episode we review the Epstein scandal and discuss Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche’s conflict-of-interest problems, the White House challenge, and the looming role of Congress.

This is an edited transcript of an episode of “Executive Functions Chat.” You can listen to the full conversation by following or subscribing to the show on Substack, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Jack Goldsmith: Good morning, Bob.

Bob Bauer: Good morning, Jack.

So, this morning, we're going to talk about the Epstein scandal and how the White House is managing it, how the Department of Justice (DOJ) is managing it, and how Congress should be thinking about it. You've been writing about this the last few weeks, so why don't you just start off by—everybody knows about the scandal, but just briefly summarize where we are.

In the last week or so, I don't know how many days ago it was, the Department of Justice became very much involved with the deputy attorney general flying to Florida for a nine-hour interview under a limited grant of immunity with Ghislaine Maxwell, former paramour and longtime associate of Epstein who has been convicted of participating in and facilitating sex trafficking, and she's now appealing those convictions.

The administration apparently thought at the time it had come to show that it was taking an active interest in disclosures after the uproar in his own base and among his own MAGA community over the surprising announcement that after a review of the files, DOJ had concluded that Epstein had in fact committed suicide, he had not been murdered, and there was no additional information to suggest that other people had committed crimes.

And as you know, from this point forward, the administration has been scrambling to address the frustrations of that community over the absence of the disclosures that they believe they were promised—the further disclosures about Epstein and those on the so-called list, those who were involved with him.

Okay, before we turn to White House management of this and other scandals, you mentioned that the deputy attorney general had gone to interview Maxwell. Talk about how unusual that is and the problems you see with that.

In my view, exceptionally unusual. There may be some cases that are comparable. I can't think of what they are. His role under the general organization of the Department of Justice is to manage day-to-day operations of the Department of Justice and to engage in overall supervision of the department's operations, not to, for example, assume specific investigative functions.

In this case, he has done just that. He is a source of information under his own name from the administration about the status of the investigation. In the case of Maxwell, who is a central figure right now, he personally interviewed her. He flew to Florida and spent a couple of days, nine hours total, interviewing her and finding out what it is that she would say if she were to testify publicly under some immunity.

We'll talk about potential clemency in a few minutes. For the deputy attorney general to do that is extraordinary. Plus, let's take something else well known: He’s a former personal lawyer to Donald Trump. Under departmental regulations, ethics regulations, his activities here implicate what is called the rule of impartiality. His involvement, having been so close to Trump, would trigger in a reasonable person a genuine concern about whether he could act impartially in this matter—whether he's actually serving the American public or serving the political and personal interests of Donald Trump.

And do we have any reason to think that he or the department are taking these ethical and conflict of interest rules seriously?

No. On the information we have, they're dismissing them. Normally, the employee who would have a legitimate concern about these issues or who would be faced with the rules’ indication that he should be concerned with these issues would seek the counsel of ethics officials in the department and then make a decision about whether he was disqualified from engaging in these activities.

When the department was asked, however, about his role—particularly in light of his telling the Senate he would ask the appropriate officials about any potential conflicts during his service—the department refused to answer. It didn't indicate that he'd asked for that advice, much less that having asked for that advice, he was cleared for the assignment.

Okay. So, I mean, that by itself would be big news in a normal administration, but this is clearly not a normal administration on these dimensions. Let's talk about White House scandal management generally. I mean, you've been inside the White House. You've had to deal with political controversies. How would a normal White House be thinking about managing this? And I just want to underscore something you said earlier.

This is largely a self-inflicted wound as far as I can tell by the administration. I mean, the main constituency that has raised this in the public profile are the president's own supporters. And as you said, it was his administration's kind of not being candid or talking out of both sides of its mouth about what was in the Epstein files, what they were going to do with it that led to this. So I guess one point is you want to avoid the scandal from happening, but how do you manage it after it gets going? How does one manage it?

First order of business is discipline. You may have a strategy that you have to revise according to events. It's not that you can have a fixed strategy in response to a scandal which is moving quickly and just stick with that strategy all the way through. There may be adjustments that have to be made, but everything you do in setting the original strategy and adopting adjustments has to be done in a disciplined fashion.

And looking to establish credibility on the part of the administration in the response to the public over the scandal, that discipline is wholly lacking. That's hardly a surprise. The president talks almost compulsively on this topic. He seems frustrated with the questions that are being asked, but he ultimately not only answers them, but he keeps going—most recently in explaining how it was that he broke with Jeffrey Epstein over Epstein allegedly poaching employees from Mar-a-Lago for potentially his own nefarious purposes.

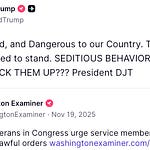

And so the last thing you want a president to do, or the administration as a whole to do, but in this case the president personally, is to feed the scandal and to do so in an undisciplined way that rather than settling questions, raises more of them. So that's the first order of business. His true social compulsions here, his speaking compulsions, are antithetical to any kind of disciplined scandal management strategy.

How would you normally manage, if this problem has a dimension in the White House, but it also has a dimension in the Justice Department, which in many ways has brought the scandal onto the administration, how would that relationship normally be managed in this context?

With some care, because first of all—and that's gone by the boards in this administration—to the extent that there are significant residual criminal legal issues here, you would want the Department of Justice to be able to claim or to show that it's operating with professional independence from political pressures from the White House.

And it can't do that in this case. That's not the way that the president has set up the Department of Justice. We've already discussed the problematic role of the deputy attorney general in this case. So you certainly would not want the department to be in the position this one is, which is it's not credible in helping the president answer these public questions.

I should mention also, I just want to tag on to what I said about Truth Social, there are other ways in which Trump has sort of very impulsively resorted to the standard playbook, underscoring again the lack of discipline.

An example being immediately suing the Wall Street Journal for defamation for publishing an article he didn't like about this scandal. And it's very clear the Wall Street Journal has no intention of backing down. That's problematic for reasons that I've written about.

And then also engaging in activities of one kind or another that are meant to be a distraction from the main charge. And all they do is focus attention on how little he's succeeding in distracting attention.

So the release of the Martin Luther King assassination files, the suggestion again that criminal behavior was not only involved but headed up by President Obama in the last administration in connection with the Russia collusion matter. These kinds of distractions—even that matter, I should add this is important—that anything damaging in the Epstein files was actually fabricated by senior Democrats, Hillary Clinton, James Comey, Barack Obama.

So he's lurching around looking for these distractions. All of this has helped him in the past, but it's not helping him here.

As you point out, one of the problems is this is really important to his constituency. Let me just play devil's advocate on that. Are you sure it's not helping for that constituency? I just don't know how to ascertain that. I mean, these are issues that are playing to the base clearly. And are you sure that if it doesn't seem, it might not seem very persuasive to us, but it might seem persuasive to the constituency he cares about?

The constituency he cares about is willing to hear for the moment that he's not trying to protect himself, that he's not involved in the Epstein files, but they want to see the files. They want to see the files because they're convinced that there are powerful people, particularly Democrats, whose involvement with Epstein has yet to be revealed.

So they're willing to split him off from that for the moment. They're angry at him for not releasing the files, but not necessarily convinced that he's trying to keep some revelation about himself out of the public eye.

But as far as I can tell—and today there was an interesting piece about this, an opinion piece by a Republican pollster and commentator, Kristen Soltis Anderson, in The New York Times. This is squarely within the concerns of his constituency: that this is a world, the world that they see, in which elites help themselves, protect themselves, and in this case, in a particularly salacious, shocking, and disgusting fashion.

And they want answers, even if they don't want to believe, and don't currently believe, that Donald Trump himself is involved.

Okay, talk about Congress and what it is doing and should be doing.

Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, have called for the release of the files—of course, on the Republican side, and particularly in the House. The speaker is playing a little bit of defense for the president. But the House has subpoenaed the files, and the Senate has made a move among Democrats to utilize a quite obscure provision.

I wasn't aware that it existed, but on its face it would appear to allow a certain number of the Government Affairs Committee, and then the House Oversight Committee (if I have the committees correctly named here), to demand from any agency the release of information that they want about the agency's operations.

So, on the face of it, it would seem like the votes would be there for the Senate, the relevant Senate committee, to ask for this information.

Here's the play, as far as I can tell: The administration will not agree to this. They will not agree that the statute authorizes this congressional demand. But now they have to refuse it. They have to refuse it.

And so it's another instance in which they've been called upon to release the files, and they won't. On the House side, most of the action there centers on Ghislaine Maxwell's testimony, and the question of whether or not she will be granted immunity, which the committee says it will not give her. And that's, again, a Republican-led committee.

And the lawyer for Maxwell is saying, well, okay, here's the fastest path to testimony: the president should give her clemency, and then she'll testify freely.

So here is the moment of truth in many respects. Here's a leading figure—not somebody with a huge amount of credibility, to be sure (and I'm understating the case)—but people's access to the information that she claims to have is going to be, to some degree, controlled by a presidential decision on a grant of a pardon.

And so how do you think this President is thinking about that? I mean, he has not been shy about exercising the pardon power. He can easily do it. So how do you see it playing if he does pardon her? Because I can imagine that raising problems and maybe providing solutions, and I can imagine not pardoning raising problems and providing solutions.

Yeah, so it seems to me it's very complicated in a variety of ways. First of all, the one person who knows what she would say is the deputy attorney general, who's presumably briefed President Trump on the contents of her potential testimony—at least her testimony to him over that nine-hour period.

So the question is, does he want that testimony out? Now, if it's out and it's helpful to him—she says, for example, that he's right, he never really had a close relationship with Epstein—that's been his claim. The problem is going to be that she's not a credible witness. So I don't know what he gains with that, although it would be a sensational moment.

Or he refuses to pardon her, and the House continues to refuse to give her immunity, in which case he's blocking the testimony and will only fuel suspicions that he's doing it for a reason: to protect himself or to protect others whose identities would be disclosed by release of the files.

And to back up and ask you about that, you referred to those nine hours as testimony. What exactly was the legal context for that discussion between her and the Deputy Attorney General? Do you know what was the context for that? What did the Deputy Attorney General purport to be doing there with someone who's been convicted by the Justice Department? The case, I think, is technically closed, although it's on appeal. What was that conversation ostensibly supposed to be about?

It was a show on the part of the administration that it was going to double-check the conclusion that so enraged its base—that there was nothing more to see, there were no more crimes to be revealed.

By the way, I should add, the base isn't only looking for crimes. That's the problem here. It's looking for full disclosure, whether the behavior in question was criminal or not. But they're taking the position that they're going to take another look to make sure that there are no other crimes.

And so, with a limited grant of immunity for the purpose of that particular interview, he presumably asked her, with names included, to go through everything that she knew about those who were close to Epstein—but again, presumably with a focus on whether any crimes were committed that have not so far been prosecuted.

That's the legal context. It's not enough, in my view, based on everything I'm seeing in the MAGA community, to address the demand they have for full release.

And also, doesn't he have to now disclose to the community? First of all, I don't even understand the context. I don't understand how it would be recorded inside the Justice Department that the Deputy Attorney General was going to talk to someone the department convicted over what. But isn't there some expectation now that he'll have to disclose the contents of that conversation, or isn't that yet another element of cover-up?

No, absolutely. It's not at all necessary that he disclose it. They could conclude in summary terms that he heard nothing different than the massive review of the files that took place earlier this year. Hundreds of department employees under his supervision apparently went pouring through the files, looking for names including Donald Trump's.

And it was on that basis that they concluded—or at least publicly announced, took the position—that there was nothing more to see there. He could affirm that. He could say, I interviewed her for nine hours.

Why is that any more credible than the Attorney General saying there's nothing there?

It's not any more credible.

I think it's making it worse for them.

That's correct. And by the way, here's something you and I have written about: there's a regulation at the department that would have permitted the requisite distance—at least in theory, depending on who was appointed—to be established, and those were the special counsel regulations.

The likelihood that the President would appoint a special counsel in these circumstances, or that the Attorney General would recommend it, is below zero. But to have his former personal attorney, with the complex issues that his involvement presented, announcing that he took another look at it and nothing was to be found is not going to be convincing to the people who are currently clamoring for the release.

Last question. What other tools does the administration have? There have been discussions. Some people have proposed that the Attorney General be fired. Does the administration need to take some dramatic step like that? How do you see this? How could they possibly resolve it successfully at this point?

It's difficult to say right now, and things could change, so my answer to the question would vary with the circumstances. But first of all, there's always the heads-rolling sort of answer to a controversy like this—some combination of a meaty disclosure coupled with firing the people who prevented it in the first place.

As you know, there are some on the right who have been calling for the firing of Attorney General Bondi. That's one thing, and it's connected to some kind of disclosure. It's connected to something that allows him to say, “Oh, big misunderstanding. Staff served me poorly. Here's the answer to your question, and the people who prevented you from hearing it have been dismissed.”

It's not clear at the moment that he has any incentive at all to fire the Attorney General. As a matter of fact, she's a loyal soldier on his behalf. I don't know that he would want to make an enemy of her, but even if that's not an issue, I don't think he wants to get rid of her.

And then, of course, if you fire her, you're then presented as an administration with the question of who you nominate in her place and get confirmed. So that can't be an attractive strategy.

And then the disclosure question brings up the last issue. It is the overriding issue—certainly for Democrats, less so for the base that wants to carve Trump out of the controversy. What disclosure would satisfy people that he's not directing attention in one place, away from whatever is in the files about him?

The Department of Justice has briefed him, according to press reports, and advised him that there are multiple references to him in the files. We don't know what those references are. The author Michael Wolff, who has written a couple of books about the administration, has recently been interviewed. He has said he spoke to Epstein, and he believes that there are embarrassing or damaging photos in those files.

So, if there is in fact something he is desperately trying to keep out of the public record, then what kind of disclosure he can offer that will answer those basic questions is very, very unclear.

All right. That's a good place to stop. Thanks so much, Bob.

Thank you.