Bob and Jack discuss (and disagree about) the Oregon National Guard ruling, the deference owed to the president, the relevance of the president’s Truth Social comments, and the ultimate limits on the president’s power to use the military in the domestic sphere.

This is an edited transcript of an episode of “Executive Functions Chat.” You can listen to the full conversation by following or subscribing to the show on Substack, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Jack Goldsmith: Good morning, Bob.

Bob Bauer: Good morning, Jack.

This morning, we’re going to discuss the temporary restraining order issued over the weekend by an Oregon federal district court enjoining the federal government from federalizing 200 Oregon National Guard members to help with a protective function—to defend federal personnel and property, mostly related to ICE in Oregon. The judge noted that President Trump had ordered the federalization of the National Guard in this context using the same authority, 10 U.S. Code §12406, that he used with regard to the Los Angeles matter we discussed a few months ago. Let me just read the essence of what that statute says.

It basically authorizes the president to call into federal service members and units of the National Guard of any state in such numbers as he considers necessary to execute the laws of the United States if he—the president—is “unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” The main question in the case is whether that trigger—“unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States”—has been satisfied, and how much deference the president gets on that point.

Basically, the federal judge said that even given due deference to the president, that trigger had not been satisfied. Therefore, a temporary restraining order was issued disallowing the federalization of the National Guard. So what do you think?

I think the court got it right. I thought the court got it right, and in a particularly compelling way. I would note—it probably shouldn’t matter to the quality of the legal analysis, it doesn’t, really, but it’s worth noting—this is a Trump-appointed judge, and the opinion is carefully reasoned. Every effort is made to distinguish this situation from the one in Los Angeles.

It seems to me that the review of the factual record, given the time the judge had to prepare this opinion, is very cautious, very fact-specific, and I think quite compelling.

So the standard—so the question is, what facts did you find compelling? Basically, I’ll summarize the facts this way: There was a good deal of violence and disruption over the summer regarding the ICE facility in Portland. The facility was shut down for three weeks. There was ongoing disruption and low-level violence, but it had definitely calmed down. Compared to earlier in the summer, there were only relatively minor events in September.

The judge said she was only going to look at recent events, not those over the summer, and that she wouldn’t consider future threats—focusing only on the last two or three weeks. You think that’s the right focus? Did I get the facts right as you understand them?

Yes, I think you did. I think by the time the president issued the directive to Secretary Hegseth, the situation was entirely under control. She details the capability of local law enforcement—the Portland Police Bureau—to work with allied state and local organizations and with federal law enforcement as necessary to bring any unlawful or disorderly behavior under control.

This is one ICE facility. The episodes had really dwindled to a handful of protests or protesters. I think she followed the same analysis the Ninth Circuit did, but arrived, within the law established in that case, at a different conclusion—and I think correctly so.

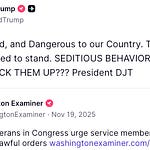

She pointed out, and I’ll stress this, that notwithstanding the record evidence that the situation was entirely under control and that the federal government didn’t have any legitimate concerns about the proper execution of the law, the president of the United States was putting out claims that were, as she put it, utterly and totally untethered to the facts. They were completely inconsistent with what anyone could observe or what local law enforcement was reporting about the conditions on the ground.

To me, the defense that the government put up lacked all credibility. I want to stress in closing here really quickly: Her emphasis on the authority ratified by the Ninth Circuit based on Sterling v. Constantine—that the president must have a colorable basis within an “honest range of judgment.” It has to be a good-faith judgment, which is absolutely critical here and in all the other cases where the president threatens to bring troops into American cities he refers to as “Democratic cities.”

Okay. So I think it’s a closer case. I just think this is a very difficult case because the president gets a ton of deference here. I agree that Trump’s statements did not accord with the facts—they were wildly exaggerated compared to what was actually happening on the ground—but I’m not sure that is legally relevant.

We can come back to that. The test that the Ninth Circuit laid down, relying on Sterling, which itself was a case about a governor, not a president, and not involving the statute, but it’s the closest case we have where the court in an emergency context questioned executive authority. So the relevance of that case ultimately is open to question.

But the court did say that, as you said, that the test was that the president’s determination could be reviewed to make sure it reflects a colorable assessment of the facts and law within a range of honest judgment. And I have to say, I just think it’s a very close case on that. And it depends on how broadly you want to expand the lens.

There was significant violence over the summer. ICE has been under attack throughout the country. There were various things going on with regard to ICE in this country.

The government claimed that its law enforcement authorities that it was using from around the country in Oregon were overstretched. And then there were small level actions against the ICE facility. So whether it’s within the range of honest judgment that the president is in that context, can make the judgment that he’s unable to, with the regular forces, execute the laws of the United States, strikes me as a close case.

And the reason it’s so difficult is, what if there’s one fact changed? What if there was a stray bullet fired in that week or within two weeks? I just don’t see how judges, absent any evidence, are going to be drawing these lines. I think it’s very, very difficult to draw these lines.

I’m not saying the judge got it wrong. I agree with you that the judge tried to apply the Ninth Circuit standard. The Ninth Circuit standard itself, it said, was underdeveloped. It was only developing it as far as it needed to in this case. So I just think it’s close and hard.

And also the government’s emergency application presented facts, and I wasn’t able to check them, that made the situation in Portland in September seem worse than the judge portrayed. And I don’t know how to assess that. But here’s the bigger picture point, and then I’ll let you comment.

The bigger picture point is that these are very broadly worded statutes, and there are many other statutes lying behind this that require these judgment calls that are factually detailed. And I just think ultimately it’s going to be very hard for judges to draw lines about how much federal law enforcement has been undermined. Although I do think this judge did a fair job. I just think it’s a close case.

Well, you and I have discussed this before privately. A hard case is always one potentially like this, where the court has to question the president’s exercise of discretion and hold that it was unlawful, as broad as it may appear to be. That’s hard.

But I don’t think this is close. And number one, I would say what took place elsewhere in the country, claims about attacks on ICE facilities or the facts of attacks on ICE facilities elsewhere in the country, I don’t think really bear on the conclusion that the judge properly reached in the case of Portland.

Can I ask you about that? Why not? If the president is seeing threats to ICE facilities across the country, and he has limited federal law enforcement authorities, and he’s being stretched thinner and thinner because of these threats, and the president thinks that threats growing in one area could impact threats in another area, especially an area that has been filled with violence before, are you saying that’s all irrelevant to the president’s judgment?

It may not be in a case where there’s good faith executive determinations to that effect. It may be relevant. But I think where there is pervasive, and I just have to emphasize this, pervasive pretextualism and evidence of bad faith, I don’t see how the courts cannot take account of that.

So I do disagree with you on the question of whether what the president has said about his reasons are relevant. I think they’re entirely relevant.

Let’s drill down. I think this is a hard issue, the president’s bad faith. I agree with you that his statements did not comport with reality. But there were facts, and there were threats to the facility. I mean, are you suggesting that a situation that is otherwise would trigger these authorities can’t trigger them because the president is mouthing off saying crazy things? I mean, where’s the bad faith coming from? Is it the president’s bad faith that infects the authorities on the ground?

The president’s bad faith goes to the question that I think she ultimately has to answer about whether the authorities are triggered under 1246. Is it in fact the case that the president is unable to execute the laws of the United States? Remember, the Ninth Circuit said minimal interference is not sufficient. There has to be—and I’m using my own adjective here—some significant impediment that local law enforcement cannot handle, even calling in the ordinary course on federal assistance, cannot handle on its own.

And it seems to me that if the president is saying these cities are burning every single night, and he used the phrase every night, there’s lawless mayhem, he’s referred to lawless mayhem. I mean, I’m stitching together a number of the outlandish claims that he made. How would that be any different, for example, just because he posted it on Truth Social, than if he delivered an Oval Office address and told the nation that that’s why he was sending troops to Portland? I don’t see how a court could ignore an Oval Office address to the American people, in which he stated the reasons why he was deploying military troops to aid in domestic law enforcement.

I’m sorry, if I could just interrupt. Does that mean if the standard is otherwise objectively met, that it’s disqualified because the president is saying crazy, false, misleading, bad faith things? Is that the argument?

I think it goes to the question of whether the standards were objectively met. I think that’s a relevant consideration if there’s evidence, affidavits, from the state, from law enforcement authorities in the state, and I think some of it’s just irrefutable evidence. We’re talking about the undeniable fact that by September, shortly before his order was issued, the situation was entirely under control.

The city was not burning. There was not lawless mayhem. He also used the phrase, death, destruction, and chaos in whatever order he did. None of that was true.

I agree. I just don’t understand, I think it’s hard to see. I just don’t understand how you operationalize that as the legal standard. I mean, do you also take into effect to—I’m just—this is a question. I don’t know the answer. Do you take into account the fact that Portland local and state officials have not exactly been robust in protecting federal property and persons in the past? I mean, how much do we have to question those representations? I just don’t understand how statements kind of outside of court, when they’re facts before the court, should impact it. I agree that the bad faith of the president is going to influence a judge. I’m just wondering how—if there was bad faith in this case and how you operationalize that test.

Well, that’s why I said these cases are always hard. I just don’t think in this particular case it’s close. And, of course, it’s a challenge for the court to operationalize it. But where you have what I’m just going to have to refer to is pervasive bad faith. You know, cities war-torn, war ravaged, you know, death, destruction, chaos. And there’s nothing of the sort.

And, in fact, if I’m not mistaken—and I hope I don’t have to be corrected on this score—the record also reflects communications between federal law enforcement and state law enforcement that confirm that the Federal Protective Service was not, at any point, keenly worried that there were not state and local resources available with some normal federal law enforcement assistance to contain the situation. So what the president said is completely untethered to the facts.

Not mildly, lightly—

I agree, I agree.

I still haven’t heard why that’s—how that—when you’re writing the opinion—why that’s legally relevant if there are facts for which there are declarations that would otherwise meet the legal standard.

But what are those facts? As she points out, none of the evidence—again, I don’t have the opinion in front of me, so I’m operating from memory. She points out that the affidavits submitted by the government were from those who were not on the scene. Again, I’d have to go back and take a close look at what the defendants had to say here. But I thought she demonstrated, in her opinion, how you can very carefully, as part of the factual record, take into account the complete disconnect between the president’s claims about what was taking place in Portland and the facts on the ground.

And they are—We’re going around in circles here. I agree that there was a complete disconnect between what the president said and the facts on the ground. I just think it’s—again, I’m not saying the decision’s wrong. I think it’s a very close case if the standard is to make sure that the president’s determination reflects a colorable assessment of facts within a range of honest judgment. I don’t think the president’s being honest in his Truth Social posts. I thought that the government presented evidence that was close on that score, especially if you’re given the context.

Now, there are legal questions here. Are you allowed to think about future threats and the likelihood of future threats? Are you allowed to look at resource constraints on federal law enforcement authorities outside? How much are you allowed to take into account past events in assessing the danger here? The judge, as a matter of law, kind of excluded all of that and just basically focused on September. So that’s a legal question. I’m not sure that’s right either.

And again, I’m not saying that the judge got it wrong. I think she faithfully and carefully tried to apply the Ninth Circuit standard. I just think it’s very close on the facts. That’s all. So let me—I mean, you can respond to that, and then I have some other questions to ask you.

I think I’ve said probably all on that particular point that I need to say here within the confines of our video chat. But I think that she closes with an important point, which is, if this is OK, then as a practical matter—and I’ll be writing about this as I know you will be, we can spin out some hypotheticals—there will be absolutely no role for the judiciary to address pervasive, politicized, personalized bad faith in the presidential deployment of troops in the homeland. There just won’t be.

And she points that out. I think she makes it very clear, if this is OK, then it isn’t clear where the line could ever be drawn.

OK, it’s important to remember that the authority that the president is asserting here is not a law enforcement authority. He’s not using the troops for law enforcement. He’s using the troops to protect federal property and federal operations and federal persons.

So that’s one point. The second point is, if she’s right about that, the president has many, many, many more powerful tools in reserve that he can use. I mean, the Insurrection Act is much more broadly worded.

The triggers are lower. The discretion written into the statute that the president gets discretion on the triggers are easier to meet. And that gives the president a law enforcement power.

And he also has the protective power under Article II that he can use not for law enforcement, but for protecting personnel and property. Again, the president’s bad faith, I don’t have—I have no doubt that the president spouts off in bad faith, or I’m not even sure it rises to the level of a bad faith. He just spouts off about what he thinks the reality is.

But there are a whole bevy of legal authorities behind this that are easier to satisfy and give the president more robust authorities. So I think if the president wants to go there, he’s going to be able to on the basis of minimal violence in the country. And you and I, you know this because you and I spent four years trying to reform the Insurrection Act precisely because it was so open-ended, so unchecked, and because the deference to the president was so great.

So I didn’t find comfort or much guidance from that closing from the judge because the president has many more tools to use here.

Well, she was speaking, of course, to the use of 1246. And there are other authorities she wasn’t addressing. But first of all, the president—the government was making the claim that law enforcement had completely broken down.

It is true that the directive to Hegseth, if I remember correctly, was focused on the protection of federal facilities. But the broader claim that the government was making was that the city was falling apart and normal law enforcement was failing completely, both in the—

The government in the briefs said that the city was falling apart?

I’m not speaking to the brief. I’m speaking to just the general claim that Portland was burning down—

Yeah, the president’s claim.

The president was claiming—That’s a claim about a complete collapse of order and law enforcement.

The president’s claim, yes, right.

Yes, exactly. And by the way, the disconnect, again, between the public claims about what was taking place in Portland and this narrower focus on the protection of a federal facility I’d like to address in two respects. First of all, that also goes to the question of good faith.

On the one hand, he’s saying that the city’s in flames. On the other hand, he’s saying he’s only sending troops to protect the ICE facility. That seems a little incongruous because he’s not just sending the troops to protect the ICE facility.

And secondly, the record, it seems to me, is pretty clear that this ICE facility, this is one location. And yes, there were arrests made. There was unlawful conduct. There was disorderly conduct.

Number one, it was brought under control. And number two, by the time that the federalization order was issued, we’re talking about a handful of protesters.

And no, none of that’s to be taken lightly, but certainly nothing that would have justified sending the National Guard into Portland.

I agree with you as a practical non-legal matter. I mean, it didn’t seem like this rose to the level to require any sort of federal militarization. Again, I’m just repeating myself. I think the legal standard is very, very favorable to the president and that he’s just getting started. He has many more authorities in reserve.

But can I ask you a question as we close? We’ll both be writing about this, but so what is the limiting principle here? Let’s assume that the president says that a particular democratic city is run by the lunatic radical fringe, that laws are being selectively enforced against Republicans and against Democrats, and there is no longer any plausible, impartial, lawful enforcement in that jurisdiction.

And he, therefore, is sending troops because he doesn’t trust local law enforcement or state law enforcement to do the job. That’s what he judges to be the case. It’s a radical, lunatic, America-hating city, and law enforcement is not to be trusted.

And there’s evidence all over the city that it’s being partially administered against Republicans and partially administered in favor of Democrats. And so he’s sending troops. That’s his assessment.

I don’t think that comes close.

Administration officials saying that’s, in fact, what they’ve observed.

Oh, well, I mean, again, is there has there been I don’t really understand the hypothetical. I don’t think Trump’s representations suffice because I think they’re false.

The question in these cases is, what are the facts on the ground? And do the facts on the ground meet the legal standard? And I’ve been trying to suggest that I think this is a close case on the legal standard. I agree with you because the president gets so much deference and because there was residual violence and unrest and because federal law enforcement authorities were stretched and because of the other factors I mentioned.

I don’t know what I don’t the limiting principle is. I think the standard that the Ninth Circuit laid down is a pretty good one. Whether it reflects a colorable assessment of the facts, not the president’s crazy rants, but the facts and the law within a range of honest judgment.

I think that’s a pretty good test. It’s not an objective test. Different people have different views about that.

So let me just let me underscore here. And again, you and I talked about this a lot for the last five years. When you take into account this statute, 12406, plus the president’s protective power.

And again, we’re talking about the president using as a legal matter these to protect federal facilities, not law enforcement, but protection of federal facilities and property. But when you take into account the president’s other authorities, especially under the Insurrection Act, minimal violence and minimal interference with the law enforcement function triggers those authorities. And we’ve acknowledged this and things that we’ve written before.

So I don’t think there’s much of a limiting principle, ultimately, if the president wants to exercise these authorities. This is why these authorities are so incredibly dangerous and why we work so hard to try to tighten them up.

One question and then one comment. The question is, I take it that at some point, bad faith on the part of the executive would be a basis for the court, a court in reviewing the assessment of facts to conclude that honest judgment was not brought to bear on the employed deployment and the statutory requirements were not met. You would agree that bad faith has some role in the court’s assessment?

But I’m trying to pin you down and I don’t know the answer on what bad faith you’re talking about. I agree with regard to the bad faith about the facts presented to the court. I’m unclear. And the Supreme Court, I think, has said this also. I’m unclear about whether the president’s true social rantings that are detached from reality bear on that. I just don’t know the answer to that.

I agree that there has to be a good faith/bad faith assessment of the facts on the ground, the real facts, whichever ones are legally relevant presented to the district court. I completely agree that bad faith is relevant there. I still don’t understand how the president’s rantings are legally relevant.

The president is the one who makes the factual determination. It says the president considers necessary. And if the president’s explaining why he considers it necessary, then it seems to be those rantings are highly relevant.

He wasn’t making those rants in the legal documents. I mean, the president makes certain findings and these findings and the factual basis for it end up before the court. But if you think that the court can look at all of the president’s rantings and say that those are relevant to determining whether the actual facts should be treated as facts, is that the idea?

I don’t think the court’s required to clean up the defense of the president’s position if the president’s position is so wholly defective and untethered from the facts. But again, you think the court has to hold the president to the determination that the president is called upon under the statute to make. And I think what the president has said about his reasons are relevant, and I think the court thought so as well.

But that’s obviously a point you and I will be writing about that point of disagreement.

I don’t know the answer to this. I mean, again, I’m trying to figure it out. I mean, so your view, but I keep trying this the last time I’ll try.

Right, sure.

There are facts before the court that, let’s say, clearly say that the statute is triggered. And let’s say they barely crossed the line, but the statute is triggered because there’s an adequate level of violence and unrest and burden on law enforcement. And they barely crossed the legal line.

But the president is out here saying there’s war in Portland, Portland is burning, saying all sorts of false, misleading, and ridiculous things. So what is the legal answer? The facts on the ground in the case are just above the line, suggesting that the president has the authority.

And those facts are presented to the court and vetted by the court, and they satisfy the statute. But the president is ranting in a way that’s detached from reality about this. Do you think that the court should say, sorry, the legal standard isn’t met because of the president’s rantings?

I don’t think you disagree, the court is not in a position to make an independent determination of the facts on the ground. It has to actually assess the facts or the competing factual positions presented by the state and by the federal government.

And in doing so, I think that it needs to look at how those facts are presented on both sides, the credibility with which the facts are presented on both sides. And I think the president ranting in a close case ought to be held against the government. I think the constitutional stakes here are extraordinarily high.

I agree. I agree. I agree.

So just to be clear, the answer to the question is yes. The facts as presented to court and vetted in court get you just over the line. The court, because the stakes are so high and because the president’s rants were so crazy, might view that as a way to deny the presidential authority.

I think in some circumstances, it would definitely shape the court’s judgment about whether the facts are over the line.

Fair enough. OK. We’re both going to be writing about this this week, and we’ll talk about it again soon. Take care.

Absolutely. You too, thanks. Have a good day, bye.

Bye.