Jack talks with University of Minnesota Law School professor Alan Z. Rozenshtein about how artificial intelligence could reshape the modern presidency by easing bureaucratic limits that have traditionally constrained presidential control. Building on Rozenshtein’s lecture, The Unitary Artificial Executive, they discuss how automated decision systems might function as a presidential “oracle” across the administrative state. The conversation examines how, and to what extent, AI could centralize power throughout agencies, reduce the role of human deliberation, and alter traditional principal-agent relationships inside government.

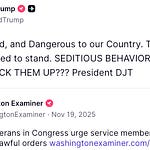

Mentioned:

“The Unitary Artificial Executive” by Alan Z. Rozenshtein (Lawfare, Oct. 30, 2025)

Thumbnail: Abstract virtual artificial Intelligence interface with human head hologram on USA flag. (Pixels Hunter, Shutterstock.)

This is an edited transcript of an episode of “Executive Functions Chat.” You can listen to the full conversation by following or subscribing to the show on Substack, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Jack Goldsmith: Today I’m having a chat with Alan Rozenshtein of the University of Minnesota Law School. Alan gave a lecture at the University of Toledo this fall on executive power and artificial intelligence, and he published the lecture on Lawfare. I had Alan come to a seminar I taught this fall.

The thesis is really interesting, so I thought we could have a good chat about it. So, Alan, why don’t you just tell us about the claim and what follows from it, and we’ll go from there.

Alan Rozenshtein: Sure. So, the claim in a sentence is that near-term—so I’m not talking here about artificial general intelligence or superintelligence, but the next three-to-five-years’ level of artificial intelligence—is going to, or at least has the potential to, massively increase the president’s control over the executive branch, and that has a lot of political and legal and normative implications that are worth unpacking.

But the core descriptive and predictive claim is that—and just to give a little bit more context—so we’re having this conversation on Monday the 8th in the afternoon, and just this morning the Supreme Court heard oral argument in a case about the president’s power to fire heads of putatively independent agencies. And it sounds like the Supreme Court, based on oral argument, is going to overrule Humphrey’s Executor, this really important case—almost 100 years old now—stating that Congress can make heads of certain agencies independent. And this is going to be a really big deal when it happens, and con law professors are going to talk about this forever, and it does matter.

But I think it’s useful to think about what the practical implications of this will be—like what the practical implications of having a, quote, unitary executive, which is this idea that whatever powers the president has under Article II, they’re the president’s powers, and so he or she has to be able to exercise them, and that means firing people basically at will.

And directing their actions and firing them if they don’t.

Exactly, right. So, you know, a few months from now the Court’s probably going to overrule Humphrey’s Executor, and we’re going to have a, quote-unquote, unitary executive. And what is that going to mean? Well, it’s going to mean important things.

It’s going to mean that the president can direct the head of really any agency—probably not the Fed, but that’s a separate conversation—but basically any agency to do what the president wants. And if not, the president can fire that person.

Nevertheless, I think that even under such a world, the president’s actual ability to run the executive branch—not just the cabinet officials or their deputies, but the, I think it’s something like three million civilian employees, and then obviously a couple million more in DOD, in the military—these millions of individuals, the bureaucracy, the civil servants, the quote-unquote deep state—the president’s powers, even under a fully unitary executive system, are still going to be quite limited, right?

And there’s a wonderful quote from Harry Truman. This was, I think, in 1952 on the eve of Eisenhower’s inauguration. Truman was giving a press conference or interview in the Oval Office, and he said something like, “Poor Ike, he’ll sit here, you know, behind the Resolute Desk, and he’ll say, ‘Do this, do that,’ and nothing will happen. It won’t be anything like the Army,” right? And the idea is just: it’s really hard, just as a matter of logistics, to oversee all these people.

And my argument is that this is actually not a legal issue. This is a managerial issue—or to put it another way, a technological, a technical issue. And one thing that AI is going to be able to do is that it’s going to be able to solve that issue. It’s going to take this unitary executive, which has always been kind of more of an academic theory, and it’s going to make it into a reality, really for the first time in American history. And that’s going to have a lot of implications—some good, a bunch bad—but that’s the idea in a nutshell.

So how exactly—I mean, what is the mechanism whereby—first of all, first of all, let me say, I’m not so sure how far the Court is going to go in saying the president has control over every agency all the way down. But set that aside. Let’s just assume that’s so, because that’s not really your point. Just tell us what you mean by artificial intelligence and tell us what the mechanism is whereby the president is going to be able to use this tool to assert more robust unitary control.

Sure. So by artificial intelligence, I’m referring to the sort of last, I’d say, ten years or so of machine learning, as it is expressed in chatbots like ChatGPT and Claude, but in particular in what are sometimes called agents. So these are artificial intelligence systems that can actually take action.

Now, obviously, right now, the only action they can take is the control of a computer, right? They’re not yet embodied in robots. I think one day they will be. And I think especially when that gets into the military domain, that’s going to raise some really tricky, sticky issues. But let’s put that aside for a second and just talk about control over a computer. That’s what the main labs are trying to do.

And the reason they’re trying to do that and the reason they’re spending hundreds—literally hundreds of billions, if not at this point trillions—of dollars in investment in the ability for an agent to control a computer, I mean, part of it is because they themselves are coders—they want to make their jobs easier. But their view, and I think this is largely correct, is that if you can automate computer work, then you have kind of automated a lot of white-collar work.

And certainly the management of the executive branch happens—or you can imagine the management of the executive branch largely being—the management of a set of computer systems, right? I mean, the executive branch is largely managed through writing memos and sending emails and organizing meetings and that sort of thing. So if you have a system that can do that—and can do that not just over a five- or ten- or fifteen-minute time horizon, as the current agentic systems can do, but can really plan over hours, days, weeks, months—and can do so not over one or two or three people, but over thousands or hundreds of thousands or millions, then you have the ability for the president to really control, at a level of granularity, the executive branch in a way that right now relies on human beings.

So another way of conceptualizing this is: what if instead of having to rely on a bunch of fallible humans, you can rely on much less fallible AI systems, whose preferences you can match much more closely to your own, to not just be your chief of staff at the high level, but get your tendrils down into all parts of government?

So is the idea that—I mean, I still don’t quite understand the claim and maybe a concrete example would help—but is the idea that computers that are going to reflect the president’s will are going to replace human beings in the executive branch, or that the president will be better able to control and direct human beings because he’ll be able to—because the computers will be able to reflect his will better? And what’s an example?

Sure. So I think both of those are true. And so I can give you an example of each one.

Right now, the way decisions—so let’s talk about the first one, which is using computers to actually control what actually happens. So right now, the way that decisions are made in the executive branch is that different bureaucrats at different levels come together and create a memo. And if they can solve that issue at that level, they try to do it at that level. And if not, it kind of bubbles up and up and up. And at some point you get to the deputies committee and principals committee and the cabinet.

And every once in a while, a decision is so important or so difficult that it has to go up to the president’s desk. Now, the higher that decision goes, the more personally the president can take control over that, either himself or through his close subordinates. But the vast majority of decisions are made at a very, very low level. And it’s very hard to oversee those decisions.

So imagine a situation in which you had a set of agentic systems that were trained on the president’s preferences—and we can talk later about sort of what I imagine that looking like. And instead of bureaucrats themselves deciding, “We’re going to resolve this issue by ourselves at our level”—and these are going to be a lot of career bureaucrats, these are people largely not politically appointed and therefore possibly working independently or even averse to the president’s own priorities—what if instead those bureaucrats have to clear their own decisions through this computer system? They have an oracle that they have to consult before they’re allowed to institute any particular policy. So that’s one way in which you could have the kind of machine implementing some of these policies.

So let me make sure I understand. So every bureaucratic decision of any—whatever magnitude—has to get signed off from the oracle, which will be trained on the president’s preferences. Therefore, the president can exercise perfect control over his agents in the executive branch. Is that the basic idea?

Yes. Certainly a lot more control. Now, you could imagine this going even further where you—so my example was kind of about the policymaking functions of government. In fact, the vast majority of what the executive branch does is adjudications of one sort or another, mostly informal. And so probably 99 percent of what the executive branch actually does—not necessarily in importance, but just in volume of action—is that.

Already, there’s a lot of interest in making automated decisions, either because they’re viewed as more efficient or they’re viewed as more accurate. But another reason that a president might want the executive branch to run much more in an automated decision way—and here I’m referring to the person making the social security determination, the person making the immigration determination, the person making the excise tax determination, or whatever the import fee determination is—another reason why the president might prefer a lot of that to be automated is that that can be controlled much more centrally by him.

Now, I think in the extreme case, you still probably need human beings—again, partially because AI systems aren’t well embodied yet. Also, at the end of the day, the courts are probably going to require a person to get up in court and say, “Carbon-based life form here representing the United States.” But certainly, even short of that, you can get a lot of centralized control over the bureaucracy.

So tell me more. I mean, let me give an example. Think about the Venezuela boat strikes. Trump said at some gaggle like a week or ten days ago he wouldn’t have wanted to take the second strike. He said that. Hegseth may or may not have been in the loop. The JSOC commander did the second strike. We still don’t know the facts very well.

I mean, how confident are you that in the next three to five years an AI system trained on the president’s preferences would have been a perfect agent there in instructing the JSOC commander whether to take the second strike or not? Let me put it another way. I’m a little skeptical. I’m a little skeptical that we’re going to have systems in the next three or five years that are going to be able to train on the president’s preferences—I’m not even sure how you do that—and to reach decisions that are reliably reflective of the president’s desires as agents.

Yeah. So I think here it’s worth emphasizing that all of these claims about whether AI is, quote-unquote, good or bad at something—and I probably was sloppy earlier, so I should fix that, so you’re good to push me on that—they’re strongest when they’re comparative claims, right?

So the question is not so much, “Is the AI going to be a perfect agent?” right? Any more than: is Spotify the perfect DJ, or does Netflix perfectly predict the next sci-fi show I want to watch? It’s relative to the existing alternative and, at the cost, are they better? And are they sufficiently better that they’re worth the switching costs? And are they sufficiently better that it’s worth it for people like you and me who care about the executive branch to think this is going to be important going forward?

That’s a great point. You’re right. It’s about which is relatively better, but just play it out for me, just using the example I gave.

In one scenario—we still don’t know quite what happened—but there was pre-planning. This was the first strike. It was September 2nd. There was pre-planning. There’s probably lots of operational planning. There was consultation between the SecDef and the JSOC commander, tons of preparation on the ground. Trump was probably in the loop at some level, but maybe not terribly tightly into the loop.

But the AI would have been trained on the president’s preferences, and I’m just wondering why you think the AI would have done a better job in deciding that second strike in reflecting the president’s preferences than Hegseth and JSOC’s coordinated activities. Just flesh it out.

Yeah. One thing that’s very tricky when you’re thinking of Donald Trump in particular—and he’s the president, so he is naturally the example—is his preferences are unstable.

That’s kind of what I’m getting at.

Right. Yeah. So for issues like this, and especially high—I think AI is going to be least interesting in situations like this, which are very high salience, in which the president’s preferences are probably fairly easily understandable, to the extent that they exist—and again, I’m not sure they even necessarily exist—by the people around him.

I don’t want to be unresponsive to your point. My sense, based on what I know about Donald Trump, is that were it up to him, he would absolutely have taken that second strike, right? The double tap is great. I think he doesn’t like drug smugglers, if these were in fact drug smugglers. He doesn’t have a lot of respect for law, whether of the domestic or international variety. He likes to look tough, all these sorts of things.

But at the same time, he likes to avoid bad PR. And so probably the best outcome for him would have been: take the double tap if you think this won’t get me in trouble, and the blowback won’t come, right? Now, that is a predictive judgment, and there’s no guarantee that any system, human or AI, would have gotten that right.

The question is, when you look across the broad range of activities, and especially those activities that are not so high salience, and right now there aren’t politicals spending a lot of time trying to figure out how to make their principal happy, will AI be better than the currently existing alternative? I think there’s at least a strong possibility that the answer is yes, yes to that.

And so what will the AI train on? What will it look at? Every speech ever given, everything ever written?

Yeah, so what I would imagine is that there would be two main sources for the AI to generate a set of preferences. One is existing public remarks. So again, the whole corpus of speeches, public statements, tweets, that sort of thing. And obviously there’s going to be some filtering because people evolve over time.

The AI can figure that out.

Yeah, it can figure that out. It’s not that hard to weight things that are closer in time versus things that are farther in time. So that’d be one source.

And then the other source I would imagine is a kind of updating feedback loop, where what you would want to do in the White House is you’d want to have someone who samples from the AI decisions that have been made recently, and then presents them to the president and asks for presidential feedback on that. So you would probably need this kind of feedback loop to avoid too much preference drift.

Now, I’ve not been part of the White House policy process, but I assume that something like this has to be happening. I assume that a big part of what the chief of staff does is sit there and make sure that the current system is properly reflecting the president’s preferences, and then makes tweaks to that system as it occurs. I’m just suggesting replacing that with a machine.

But I think the implications of your view are that all deliberation in the executive branch can just go by the wayside. And once the machine is trained on the president’s preferences, then every executive branch order will be knowable.

And what about—I mean, there’s learning from deliberation outside of what the president says and does. There tends to be learning from interagency processes, from new facts being brought to bear that maybe the president didn’t know about. What happens to all that? I mean, why do we need any deliberation in the executive branch?

So it’s an empirical question. I don’t know if we do. I think if there’s any lesson of machine learning in the last ten years, it’s that one should be very careful about assuming that there’s something ineffably special about how humans do things that AIs cannot replicate.

Now, because every time someone has said, “Oh yes, AIs can do this and this, but they can’t do this other thing,” it’s like three weeks later they can do it. And so you just end up moving the goalpost over and over again. Now, there’s no guarantee that this progresses forever, right? None of my argument depends on us waking up one morning and discovering that Silicon Valley has created the machine god.

So it’s quite possible that there will always be necessary space for human decision makers, right? I think it’s useful to think about the extreme case as a kind of stylized, you know, what is the sort of logical conclusion possible of this? And that is, you know, everything just becomes the sort of oracle and you ask that.

But the audience for my argument is lawyers and executive power types, right? For whom a 10 percent more powerful executive is a massively big deal, right? And so that’s the only point I’m making, right? I don’t have a super strong prior on how far you can push this.

Yeah, that claim seems much more defensible and likely to me—that the president, and I wouldn’t just view it as the president, the oracle via the president. I mean, it might be that—probably would be the case—that a well-informed president might want the AI to train on his—maybe this current administration is not a great example—but his specially chosen expert secretary of defense or especially chosen expert secretary of state, because the president might realize that. And then that secretary of state might want to delegate the AI to be trained on someone lower.

So you can imagine there being lots of humans in the loop and the AI decision-making happening at a lower level, which means that the humans think that there’s—if that’s true, if that’s a possible scenario—it means the humans think that there is, in fact, value in delegation.

Yeah, I think that’s all possible. And let me—let me try to describe the argument in just a different frame. This is one that is, I think, going to be less flashy but maybe more convincing, which I’m fine with.

Which is: if you want to view AI as just the next advance in information technology, where information technology has always increased the power of the presidency, I’m more than happy with that version of the argument, right? If you want to say, “Oh no, this is just a difference in degree, not in kind,” like—sure. I think it’s a big enough difference in degree that it’s worth paying attention to.

But one historical tidbit that I’ve always enjoyed is the fact that Abraham Lincoln was the first president to have the advantage of the telegraph in war. That was the new information technology of the day. And although it seems quaint right now because you’re sitting there typing in Morse code, it was huge. It was maybe the biggest technological advance of the last 200 years, because suddenly Lincoln could sit in his office in Washington, D.C., and actually be a battlefield commander.

He could go and he could send things to George McClellan, who then could happily ignore them—but that’s sort of a different story. I think there’s been interesting—and I’m curious if anyone has written this, and sort of I’m tempted to, though I’m not really a historian—to write the history of the presidency through technological transformation, right?

Oh yeah, there have been. I mean, the president’s control over communication and information gathering is a source of the president’s increased power over time.

And so AI is just the next chapter of this.

So I think that’s a fair point at a general level. I mean, it seems to me that at a minimum, that presidents since at least Roosevelt have been trying to centralize decision-making power in the White House, away from the departments and agencies, and with various degrees of control—but that’s been a clear trend since at least Roosevelt.

And one challenge to that is knowing what’s going on in the executive branch and being able to collect and analyze information. And there’s no doubt that these systems are going to allow greater information extraction from the executive branch, and greater information analysis from the executive branch, and probably more efficient White House control in issuing orders.

Indeed, you can see this as basically what DOGE was trying to do, in the sense of having a White House entity go inside of an agency, extract information, inform the White House, and then the White House can impose the order on the agency—basically a way of circumventing the agency. If that could all be automated, which is basically what you’re saying, it would definitely facilitate White House control.

That’s right. And it’s not just what DOGE was trying to do—it’s what DOGE did in a very abortive fashion, right? They sent out these emails, the famous “what are the five things you did this week?” emails.

And my understanding, based on some reporting—I don’t have any information, just based on public reporting—was that they had set up an open-source model, the Meta Llama 2 model, and they were trying to feed—or were in the process of feeding—these emails through that. I don’t know how far they got. I mean, DOGE was a sort of shambles, largely throughout. But technically, it’s not that hard.

It’s certainly a lot less data than a lot of these. I meant the DOGE as an organizational model, because there was a lot of humans in the loop there.

So here’s a different question: Why is this necessarily a bad thing?

So it’s not necessarily a bad thing if—well, okay. So as long as your president’s great, maybe it’s a great thing.

Well, I’m wondering how much you worry about this if the president is non-virtuous, or you’d madly disagree with the president’s policies, and how much you’re okay with it if you think the president is virtuous and you love the president’s policies. The president’s elected; the bureaucracy isn’t. This is another old theme in presidential history: presidents—Trump is not the first, and he won’t be the last—try to get control of the bureaucracy and impose his will on the bureaucracy.

And a lot of—you know—FDR wanted to do that. Thomas Jefferson wanted to do that. So I’m just wondering: is this necessarily a bad thing, or could it be seen as a good thing depending on the president and the policy aims?

I mean, it depends on whether you care about process or not, right? And, you know, I think one pathology of lawyers sometimes is that they forget that normal people aren’t quite as obsessed with process as lawyer robots are.

You know, I tend to think that it’s a useful thought experiment and a useful disciplining function to ask, okay, this power—if it was wielded by the other guy—how would I feel about that? And I think, at least in our age of partisanship, where people seem to hate the other side much more than they actually like their own side, that any technology that could so massively increase the powers of the president, I think that should be of bipartisan concern. Because, yeah, think of all the good things your guy could do with it—but think of all the really terrible things that the other guy could do with it.

So, yeah—again—I mean, if all you care about is the results within a particular four-year stretch, it’s a great thing, right? But that’s no different. I mean, this is just a special case of: do you like dictatorship or not, right? And sometimes there are good dictators, but the problem is: what about the next guy?

Why dictatorship? The president’s elected, and let’s assume that the AI is constrained by law. If the AI is constrained by law and the president’s elected, I don’t see why the dictatorship argument is right.

It’s really whether you like the unitary executive or not, because this is the unitary executive on steroids.

Yeah, sure. And by the way, every president likes the unitary executive to some degree—to some degree. And so I think the “AI is constrained by law” is doing a lot of work here.

So one problem is that we’re not sure how to do that, right? So there’s this idea—and there are some really interesting, smart academics who have been trying to build this out—of what’s called law-following AI, which is the idea that just as you can train an AI system to refuse to respond to certain prompts or refuse to take certain actions, you should also be able to get it to refuse to take unlawful action, right? Conceptually, that makes a lot of sense. How you implement that is much, much less obvious. These deep questions of alignment and so forth.

So there’s a technical question whether you can have a law-following AI. There’s another question—and this kind of gets back to the unitary executive part here—of whether Congress is going to be able to sufficiently regulate these systems such that they will, in fact, be law-following. I think there’s some interesting constitutional questions over the extent to which Congress can do that. I think there’s certainly going to be political will questions every time Congress will do that.

And then, of course, there is also just the more philosophical question of how comfortable is one with the unitary executive, right? Does one think, as Chief Justice Roberts has said in several of these recent opinions, that because the president is the only individual—other than the vice president, but whatever, no one cares about the VP—since the president is the only person who was elected by the entirety of the nation, he has a special democratic pedigree? Or as Justice Kagan kind of said in her “Presidential Administration” piece before Roberts did?

To what extent do you think that that is the highest essence of democracy, right? Now, you can think that—but then you’re going to have the issue of democracy policy swinging that massively between administrations. Maybe that’s okay.

There is, however, an alternate view that democracy is a much more—the democratic will is a much more complicated thing. It’s much better reflected in a balance between the president and Congress and the quote-unquote deep state—that that is a much better expression of democracy in getting at the people’s preferences—in which case, this is not a great thing.

But at this point, the argument just collapses into what do you think about the unitary executive and democratic theory more generally?

Okay, two more questions. One is, doesn’t your argument depend on assuming away alignment problems in AI?

And don’t we need to know something about that to have confidence? Wouldn’t the president need to know about that to have confidence in using these techniques?

Yeah. So it doesn’t assume away alignment problems, but the assumption it does make—which is a non-trivial one, but I think a much weaker assumption than assuming away alignment—is that AI systems are more aligned than humans, right?

So I just want to keep hammering this point home, which is: the question is never, is the AI system perfect? Or does the AI system meet some very, very high threshold?

The question is, is the AI system better than the current human alternative?

You know, we’re dealing with this debate right now with self-driving cars, for example, right? And people will point out that, you know, we haven’t solved self-driving cars. They get into accidents. They kill people. You know, they killed this cat in San Francisco—Kit Kat—and it was like a big deal. But that’s not the question. The question is relative to humans.

And so the problem for presidents and for rulers generally—which is why there’s a version of this article or this argument that you could write in China or Russia or North Korea or any government across the political spectrum—is it’s a principal-agent problem all the way down, right? The president is just one person, only so many hours in the day, right? So he relies on his close subordinates, and they rely on their subordinates.

And then you have a massive tree, and suddenly you have three million people at the very end. So it’s not, “Is it perfectly aligned?” It’s, “Is it better aligned than humans?”

And in answering that question—fair point again—I just come back to something I said before to consider, which is: it’s not obvious to me, given that uncertainty, that you don’t want to delegate, and then delegate, and then delegate even with these AI tools, because you might have more confidence in the AI tools’ decision-making authority at a lower level of greater expertise that you trust.

So to the extent that you talked about an oracle that’s deciding everything, it strikes me that even in an optimal world that may not—it may be multiple oracles embedded at different levels of the bureaucracy, based on some calculation made in the White House, probably with the assistance of AI.

Yeah, absolutely. And there’s nothing—I still think that would strengthen presidential control. Because even if you just have the oracle—

My point is, I think that would enhance presidential control over just having the presidential oracle.

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. You don’t need the president—I do think of the presidential oracle. I think of, sort of, the presidential oracle. Yeah, the presidential oracle is least useful in the Executive Office of the Presidency, right? Because by that point, the decision set is a more manageable set of decisions.

You need to train the presidential oracle in the White House because you need the president’s preferences. But yeah, where it has the most bite is when you send it out to, like—you know—the Ramsey County, Texas—or whatever, that’s a state position—but you send it out to sort of the random, kind of deepest, darkest corners of the bureaucracy.

Yep. Last question. I’m very skeptical that the U.S. government has the competence to execute this, especially in the next three to five years.

Am I wrong about that?

I mean, certainly not at the kind of totalizing level that the sort of thought experiment suggests. I think there are going to be some areas in which this is more easily implementable, right?

I think if you take sort of discrete adjudicatory places, you could slot this in, right? You know, right now it would not be rocket science to come up with a model that you feed every asylum application through to do algorithmic scoring. And you can tune that—

You know, you can tune it all the way down, right? Say no asylum if you’re Trump; you can tune it all the way up if you’re President AOC. The point is not about Trump.

So yes, I think it is fair. And I think—look—I think this is a fair critique of breathless claims about AI’s impact generally, which is that AI enthusiasts—of which I am definitely one—get really enamored by the technology, and then they kind of forget about all the sticky frictions.

So it’s totally possible this will take a long time. But again, especially given how overpowered the executive already is, I think, relative certainly to Congress—we can have an interesting conversation about the judiciary—but certainly relative to Congress, even incremental increases in power are quite dramatic.

And then, you know, of course, you never know—maybe the AI gets smart enough that it figures out the one neat trick to self-propagate its way through the entire executive branch.

Okay, Alan, thanks very much. There were a lot of issues in your lecture we didn’t talk about. The lecture can be found on Lawfare. It’s called The Unitary Artificial Executive, October 30th.

Thanks very much.

Thanks for having me, Jack.