Jack and Bob examine President Trump’s threat to invoke the Insurrection Act in response to ICE-related unrest in Minneapolis. They discuss the Act’s broad language, the uncertain scope of presidential discretion, the many unresolved constitutional questions that the Supreme Court might consider, and the political and legal risks of deploying troops domestically—particularly against the backdrop of upcoming elections.

Further reading:

“Trump Threatens to Invoke the Insurrection Act” by Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith (Executive Functions, Jan. 15, 2026)

“Thoughts on the Interim Order in Trump v. Illinois” by Jack Goldsmith (Executive Functions, Dec. 24, 2025)

“Trolling About Habeas Corpus” by Jack Goldsmith (Executive Functions, May 12, 2025)

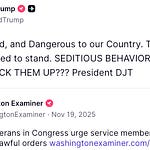

Thumbnail: Department of Homeland Security operations in Minneapolis, Jan. 6, 2026. (DHS photo by Tia Dufour)

This is an edited transcript of an episode of “Executive Functions Chat.” You can listen to the full conversation by following or subscribing to the show on Substack, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Jack Goldsmith: Good morning, Bob.

Bob Bauer: Good morning, Jack.

President Trump, a few days ago, threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act in response to standoffs with ICE in Minnesota.

Today, we’re going to talk about why he’s making this threat now and what it might entail.

Let’s begin then with what our viewers are very familiar with, and that is the Court’s interim order in Trump v. Illinois. And there the court had something to say about the authorities under which the president could deploy the National Guard. That was directly before the court, but also there was discussion of the Insurrection Act.

Can you talk a little bit about that as background for how we might expect things to unfold from here?

Sure. Without getting into the very complicated details of that order, that was a statute, Section 12406, under which the Trump administration had federalized the National Guard to perform a protective function in Illinois, protecting ICE. The Supreme Court, in a very brief but complicated decision, essentially said that the president couldn’t invoke that statute to federalize the National Guard unless he could show that the regular military was authorized to enforce the law domestically and unable to do so.

And since the president had not made that showing, the Court basically said that the president could not rely on that other authority. Now, as Justice Kavanaugh said in his concurrence in that case, and I’m reading from it now, one apparent ramification of the Court’s opinion is that it could cause the president to use the U.S. military, as opposed to the National Guard, more than the National Guard to protect federal personnel and property in the United States. I wrote about this also.

You can see that interim order as inviting the president, or at least giving the president an opening to invoke something like the Insurrection Act, which is a statute that overtly authorizes the use of U.S. military forces to enforce the law domestically.

Address, if you could, just one thing right at the outset, which is it’s an opportunity that’s always been available to the president. In other words, Supreme Court didn’t create an opening that didn’t exist before. However, by closing off this other statute, 12406, it may have, some argue, driven the president in the direction of the Insurrection Act because this other source of authority was not available.

How do you assess that?

Yeah. As you say, the Insurrection Act has always been available. I think the administration perceives, probably correctly, that the political stakes are much higher if he invokes the Insurrection Act, because that’s really a statute that’s meant for an extreme circumstance. But the Insurrection Act was available and has been available for the president since the day he became president.

So it’s not really true. And again, I tried to make this point clear in what I wrote about the interim order. It’s not really true to say that the Supreme Court is incentivizing or inviting the president to use the Insurrection Act.

And that’s not what Justice Kavanaugh was saying. Nonetheless, I can imagine the administration, if it invokes the Insurrection Act, trying to make an argument like that, they’ll certainly say that, well, the court said that we hadn’t shown that we had a statutory basis to use the military to enforce the law. And here we are using the military to enforce the law under the Insurrection Act.

Let’s talk then about how the courts might respond. So we’ve written, as others have, that this is an antiquated statute. The terms are antiquated and indecipherable.

That is to say, the so-called triggers that the president could use to invoke the statute and to deploy the military. No role for Congress, no time limits on deployment. And there’s a general sense that, well, this is once he’s invoked it, it’s not at all clear, given the broad discretion of the statute seems to confer.

It’s not clear what limits might apply in any challenge. Can you talk for a second about how you see this playing out? Because one might argue one of two things.

One might say that’s correct. The Insurrection Act seems quite open-ended and the president will receive great deference. On the other hand, as the Illinois case suggests, these cases may rest entirely on the facts and the courts may be suspicious of the grounds of invocation that the president asserts, particularly against the background of these extraordinary controversies over the deployment of the National Guard and now the operations of ICE.

So I’d be interested to get your sense of what might we expect from the courts, how how wide a playing field has been afforded the president?

So I’ll say a couple of things, as you said, I mean, the Insurrection Act, and as we’ve been emphasizing for years now, is an extraordinarily broadly worded statute that that gives the president really many predicates to call out the National Guard and the regular military forces to enforce the law. And there are some 19th century precedents, Martin v. Mott and Luther v. Borden that can be read and have been read to give the president extraordinary discretion in making the determination that the Insurrection Act predicates are met. So in that sense, just on the face of it, the president, as we’ve been arguing, has extraordinary discretion.

But a couple of caveats—several caveats, actually. One is, as you suggested, also the Trump administration has shown itself capable of overstepping, even with broad authorities given to it, of not developing predicate facts needed to implicate a statute of suggesting bad faith in the way that they’re using authorities. And then it actually also depends on what the actual facts on the ground are. And when the president is invoking the Insurrection Act, how they justify it in the executive order and the like.

So that’s an uncertainty. A second consideration is that, as we saw in the interim order case in Illinois, the court was there interpreting a statute it really hadn’t interpreted before. It was looking at questions freshly and asking foundational questions about the statute. I think that every word of the Insurrection Act is going to be poured over and the Court is going to be forced to give it — the Court really hasn’t done a deep dive into the Insurrection Act in a very, very long time.

And so I think that there are going to be some foundational issues that come up. The whole question of the deference under Martin v. Mott and Luther v. Borden is going to be looked at very carefully. There are ways to distinguish those cases when you get down into the weeds.

So that’ll be a question. And then as Justice Gorsuch sort of hinted at in his dissent in the Illinois case, there are some foundational constitutional questions that invocation of the Insurrection Act will address. I mean, do you want me to talk about those?

Yes, please.

So Jay Bybee, senior state’s Ninth Circuit judge, issued an opinion in a statement in one of the en banc Insurrection Act cases in the Ninth Circuit where he made the point that, and I’m going to be talking in both of these foundational constitutional issues, they both have to do with the Militia Clause of the Constitution. And this is the Article I clause that says Congress shall have the power to provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions. Now, that is the constitutional basis, the primary constitutional basis for the Insurrection Act.

And as we’ve discussed before, the Insurrection Act, as it’s called, is actually a series of statutes going back to the 18th century that have been enacted over time, changed and now kind of put together in one part of the U.S. Code. So Bybee raises the question about, you know, the militia clauses say that Congress has the power to call forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union. But there’s another clause of the Constitution that he points to, the Domestic Violence Clause of Article IV, which says the United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a Republican form of government and shall protect each of them against invasion and on the application of the legislature or of the executive when the legislature cannot be convened against domestic violence.

In other words, Article IV says that the federal government shall guarantee to the states of the union protection against domestic violence, but only when the states request it. So Bybee is basically suggesting that the Militia Clause has to be understood in light of the Domestic Violence Clause, basically suggesting that the president can’t or shouldn’t receive deference on the question of using the regular military to enforce the laws domestically unless there’s been an invitation by the state. That has not been the understanding of the Insurrection Act, but I think that that’s a kind of foundational question that will be asked.

A second foundational question that will be asked about the Insurrection Act is— and again, this has been long settled, but I think it will be questioned — The militia clause says that the president can call out the militia to enforce the law when needed. But the Insurrection Act has authorized the use of the regular military, not just the militia.

This was an innovation by Congress way back in 1807. The constitutional basis for saying that the regular military, as opposed to the militia, can enforce the laws domestically is not clear. It certainly isn’t the militia clause.

It’s probably the war power. So there’s a foundational question there about whether the president has the constitutional authority to send in the regular military to enforce the law. Both of these questions, I think, have been long settled by practice, but they’ve never been, to my knowledge, thoroughly vetted in the Supreme Court.

So these these are the kind of foundational questions that the court is going to have to encounter. I don’t think it’s going to be a walk in the park for the administration.

On its face, the president has extraordinary authority. That is the legal claim, and it’s a true legal claim. But the reality of how that thing gets litigated, of how the statute gets litigated and of how the administration goes about doing it, how it defends it, what the kind of narrative context is. And then all of these, we’re going to see just as we saw after 9/11 with the president’s military authorities asserted there with respect to detention, military commissions and the like, there were a lot of there was a lot of presidential support for President Bush’s unilateral actions soon after 9/11.

And three years later, four years later, the Supreme Court had blessed some of them and pushed back on a lot of others. And it turned out that precedents from World War II that looked rock solid and from the World War II context didn’t operate the same way after 9/11. And so we’re going to see that dynamic playing out.

There’s no doubt about it, that the old precedents are going to be subjected to scrutiny in a new and different context. And how that works out, I think, is just uncertain. So the real bottom line point is that the court will decide the modern relevance of the old precedents.

And while the old precedents are very strong in the president’s favor, they’re not airtight and it’s open to the court to rethink them and reapply them in a different way, in a different context. I just think it’s it’s just too early to tell how that might play out. We don’t even know if the president’s going to invoke the Insurrection Act and we don’t know how he’s going to invoke it.

We don’t know what the political context will be. So it’s hard to say how it will play out. But the administration can’t be sanguine about the Insurrection Act arguments.

And I think maybe that’s one reason why they’ve been hesitating. I don’t know.

This seems to be an extremely important point that the court may not be writing exactly on a blank slate, but it’s it’s a page on which there’s plenty of room to write. And, you know, for example, on these foundational questions, understandings that we haven’t had for a long time that could be revisited. I’m reminded of the sort of course correction or change in course that they took in the Illinois case where the understanding of the term regular forces suddenly received much closer attention ultimately was pivotal to the decision in the case.

And so I think it’s important for generally people to recognize that not only will every term in the statute be closely vetted and scrutinized against the facts of the case, but there’s some pretty deep constitutional questions that could wind up being revived in the analysis of the court and lead to some surprising results. Am I overstating the case?

No, I think that’s right. That’s what I was trying to suggest. And this may be one reason why the administration has hesitated.

I mean, on its face, the Insurrection Act is an extraordinarily broad statute. Why haven’t they invoked it yet? They could have invoked it on the same predicates that they used the other statute, which was a narrower and more obscure basis to federalize the National Guard.

They could have invoked it to actually use the regular military to enforce the law under the terms of the statute. They’ve hesitated, I think, because the politics are more fraught. I think they are — I’m not sure. I think the politics are more fraught of invoking the Insurrection Act and certainly bringing in the regular military is probably politically more fraught. But there are all of these foundational questions and that that are going to be addressed and especially in the Supreme Court.

I mean, the lower courts, as we’ve seen, are going to feel bound by Martin v. Mott and Luther v. Borden and some of these other precedents. Certainly the Supreme Court will as well. But there are ways to read those opinions that might not lead to full support for what the Trump administration is trying to do.

So, yes, there’s plenty of questions to be answered that the court will ultimately have to answer.

Yes. And there’s something else, I think, that’s going to play into their thoughts about whether to invoke it. And that is, there are polls and there are polls, and they vary significantly in sample size methodology, frankly, even credibility.

But the public is turning against the overall picture of these ICE operations. They continue to support robust enforcement against illegal immigration, but they don’t like the way this is being done.

Yeah.

And for the president in the middle of all of this to invoke the Insurrection Act with the uproar that that is going to create, I think is certainly not going to be helpful to his political standing at a time when the White House is, you know, as far as I can tell, rightly and keenly concerned about the president’s political standing in advance of the midterms.

That’s another way of saying just that the politics seem to be moving against the president on this issue, the way that immigration law is being enforced and that the politics might preclude implication of the Insurrection Act. And let me just say, they’ve threatened a lot of things in the last year. Many of them they’ve done, but many of them they haven’t done.

I mean, again, Miller six months ago came out and said, we’re thinking about suspending the writ of habeas corpus. Everybody’s head exploded. I was doubtful about that at the time for reasons that I wrote about.

But they’ve threatened all sorts of things that they haven’t followed through on, in part, who knows why, in part to gaslight, in part to play to the base, in part to discombobulate people, in part to put up a trial balloon. But the president says a lot of things in his Truth Social posts that never come to reality. And the Insurrection Act may be one of them we’re going to find out.

Yeah, I should add, by the way, I’ve always thought one other possible reason for hesitation, although that may be dissipating with time, is that the public heard a good bit about the Insurrection Act maybe for the first time in a long time in connection with January 6, when the administration, there were administration officials discussing potential use of the Insurrection Act in support of the president’s challenge to the 2020 election. So I thought that was also a sense of potentially a sensitive point.

Again, I’m not sure how sensitive the president remains to that since his his rhetoric and actions on that subject have definitely escalated. Let me ask you your reaction to other thoughts that I’ve had about the difficult posture that the administration may be in when it comes before the court if the president invokes the Insurrection Act, say, in relation to what’s taking place on the ground in Minneapolis. We’ve talked about the potential they’ll make claims that don’t hold up against the record, question of bad faith.

There are two other elements here that stand out for me. One of them is, the Court has to be sensitive to all of the attention that’s being paid to whether, in fact, the outbreak of lawlessness is being exacerbated by the conduct of ICE, whether the administration itself is creating the very conditions that it may later claim require the invocation of the Insurrection Act. And I can’t imagine that there isn’t some way that advocates in writing or in argument won’t point to that.

So let me start with that. Could that be a background concern of the Court as it thinks about the implications of the use of the Insurrection Act in these circumstances?

I’m certain it will be a background factor for the Court, but there’s another side to it. And the Court has talked about this in its interim orders, and that is the president has lawful authority to use the law enforcement machinery of the federal government to remove unlawful immigrants, you know, as long as it’s complying with the law. So they’re going to be competing narratives there for sure: that on the one side, the president ran on a platform of reversing what the Biden policy on immigration and and correcting the Biden policy on immigration.

And that’s what he’s doing. And the other side is going to say the president is using ICE in a way that is extralegal or on the borderline of legality and is creating the very situation that is being taken advantage of to invoke the Insurrection Act. I think we’re going to see competing rhetoric both in the briefs, probably, and certainly in the in the public discourse.

I don’t know how. It’s just hard to know how that’s going to play out for the Court, I think.

Yeah. And on that second point, I think one of the arguments about ICE’s conduct will be that it hasn’t simply encompassed communities where there was good reason to believe there might be illegal immigrants who needed to be brought out and faced legal process, that it has touched on the lives of American citizens. There have been videos of citizens who have been attempting to establish their citizenship but were effectively not given the opportunity to do so before force was applied.

So I think, again, there’s so much in the background here to color the understanding of what’s taking place in Minneapolis, not to mention the very sort of heated rhetoric that the president puts out on Truth Social. Another background element that I wanted to ask you about that may come up, the administration after the Renee Good killing took the position that it was not going to cooperate with Minnesota law enforcement in investigating the the death of Ms. Good and one question is whether or not someone’s going to take the position. Listen, you can’t government allege that local law enforcement, state and local law enforcement is unable to execute the law because you’re, in effect, shouldering them out of the picture.

There’s such hostility between the federal government and the state. Some of it, of course, based on the president’s allegation, it’s kind of a runaway rogue blue state. And so, again, you’re in a situation where the administration is claiming that the state can’t do something that the federal government itself is making it hard for the state to do.

Do you think that has any potential background force in the arguments in the case?

I have basically the same reaction to that as the other one, which is there’s another side to that rhetoric, which is that the federal government is claiming in all of these cases that state and local law enforcement are not being cooperative, are not being helpful, are resisting the force of federal law and federal law enforcement. I can’t, I mean, there’s so many different contexts in which these arguments come up, and I can’t sort them out. And I think it’s extremely difficult to predict how those competing narratives are going to play into the I’m not denying that they will play into the Court’s decision making.

I mean, the court decides on the law, but it’s not irrelevant. It’s not indifferent, obviously, to the reality of what’s going on in the world. I just don’t know which which narrative is going to win out and how they’re going to play out among the nine justices.

Can I ask you a question?

Yes.

We’ve written about the elections this year, in November, and we’ve written about the possibility that the president might be — and indeed, it seems clear that the president is — contemplating using federal law enforcement in novel ways to perhaps impact the election or bring about favorable results in the election or, to the president’s view, enforce election law the way the administration thinks it needs to be enforced.

Can you just talk about that a little bit and talk about how the Insurrection Act and law enforcement by the military may play into that and why we might be worried about that?

Certainly. Well, I mean, the president recently said, for example, and this doesn’t necessarily require the involvement of the military, but recently talked about sort of forcible intervention in the election process by saying he regretted that voting machines — I believe it’s voting machines, if not ballots — had not been seized in the wake of the 2020 election. And as you know, there was an executive order in draft prepared to that effect in the last Trump administration, in the waning days, as part of that that challenge to the election that was mapped out in various directions.

He has taken the position in an executive order that he issued some time ago now, promising that he would issue a second that contrary to the way the election of this country is structured constitutionally, contrary to the way fundamentally the entire legal order is set up for that purpose, that for the good of the country as president, he can, in effect, federalize the electoral process and oversee functions in the context of the election that have typically been the province of the states. So you have bellicose rhetoric and a broad assertion of authority. And then, of course, there’s the question of whether or not the president would use the military to carry out some of these interventions.

And let me just say one thing about the formal use and then the informal use and its potential effect. I mean, the formal use would be using the military to intervene on a claim that the election is being rigged, the election laws are being criminally violated. In effect, there’s been a subversion of the constitutional order and he has to call out the troops.

There are some very clear legal issues, to say the least, being raised by this, including federal statutory provisions that appear on their face to prohibit the deployment of troops to polling places. Then there’s the question of whether the president would ever recognize those kinds of restrictions. And rather, and I’m going to come back to his Article II authority question, I want to ask you still whether he’ll just invoke his constitutional authority in the circumstances, essentially issuing a constitutional emergency decree.

So there are whole sorts of issues about those kinds of direct interventions. But there’s also the question of what these kinds of threats and the mini-execution of these threats could mean for voting.

Let’s assume, for example, that the president starts to send out fevered, true social messages the day before the election, three days before the election, early in the morning of the day of the election, saying crimes are about to be committed. The constitutional order is about to be subverted. The rigging that I’ve always claimed would take place is currently occurring. I am calling out the National Guard. I’m operating, I’m invoking the Insurrection Act. I’m acting pursuant to my constitutional authority. And he puts out images of airplanes taking off and troops being mobilized.

That’s obviously going to have in some jurisdictions an extraordinarily chaotic and disruptive effect. Whether he actually acts upon it to the degree that he claims or not, of course, that matters enormously. And there will be an immediate response to this in the courts.

But the damage may have been done. And so a lot of effort has to be put in, in my view, before the election to put up every single guardrail against an attempt to issue these kinds of threats. If you take the darkest view of what he might be prepared to do to stave off the loss of the House of Representatives and maybe even the Senate in this midterm election year, I’ll just close by saying the stakes for him, he has claimed, are super high.

He’s not on the ballot, but he has suggested that quite apart from it being obviously very bad for the last few terms of his administration, if the Democrats regain control of the House, he has posited that he will be impeached. They will impeach him.

So there’s a direct personal stake in the outcome of these midterms.

I have a couple of questions about that. So it seems like a, it seems like a legal nightmare to have novel questions of federal executive authority concerning congressional elections combined with novel questions of the Insurrection Act being played out in litigation up to, during, and beyond the election, which takes place on kind of an emergency basis. Those cases always go very quickly with all those novel questions, with all those high stakes claims with it happening on a fast track.

It just sounds it sounds concerning. But you said that we should try to have guardrails in advance. But how can we have guardrails in advance to stop the president from engaging in certain threatening rhetoric, or even guardrails in advance to prevent him from trying to make these executive power gambits?

I mean, what kind of guardrails can possibly be put in place before November?

Well, of course, a lot depends on what happens between now and then. And I posit it’s sort of a last minute intervention. But some of these steps may become visible, may even be taken well before the election.

He has said he’s going to issue another executive order to supplement the first. The first was intended to extend intended to expand his authority over mail-in voting, over voting machinery that he continues to claim is unreliable over the monitoring of potentially illegal foreign national intervention in the elections. And that’s being litigated.

A second executive order or steps pursuant to the first will be litigated. So there are some steps that certainly could legally be taken and likely will have to be legally taken before Election Day itself. And obviously, you know, the earlier, the better.

I’m going to say something I’ve said before, and I think it does matter. A whole civil society response to these threats is going to be critically important. There are actors in the political process and in the broader civil society who are in a position to influence the course of events.

I mean, I’ll give you an example and how it would apply in these circumstances. I really can’t predict, but an example would be the unwillingness of the Indiana legislature to agree to the president’s attempt to have more seats added to the Republican column through a sort of mid-decade election year redistricting. These kinds of pressures are critically important.

And by the way, you and I have talked about it. Others have written about it. The response of the military to these orders is going to wind up being critically important.

And right now, the administration is trying to send a message about this more generally with its threat. First of all, it’s acted to enforce discipline against Senator Mark Kelly for advising members of the military that they are duty bound not to follow illegal orders. Those same threats have been directed and I think investigations have been undertaken of the other senators who have issued similar, completely correct legal guidance on the obligation of the military.

And so there are points in this system where those with huge responsibility and choices to make have to choose wisely. But those choices, if made wisely, can make an enormous difference.

You said you wanted to ask me about Article II.

Yeah, so let’s assume the president says, and by the way, whatever you say about the Insurrection Act and whatever, I have Article II authority that transcends all of it. It’s I can for the good of the country to restore domestic tranquility, protect against rebellion, against state and federal authority. I can deploy the military.

I’m commander in chief. And so, yes, I’m going to invoke this statute. But any responses, legal responses, you know, if they’re wound up to be in that setting deemed to be effective, do not nullify my capacity to turn to this inherent authority to accomplish the same purpose.

What are your thoughts about the —

Just so I understand, military authority to accomplish what purpose exactly?

Well, for example, to send troops into Minneapolis on the ground that the city, to quote what he said about Portland, is burning to the ground. You know, it’s chaos. We have basically civil war in Minneapolis, complete insurrection against the federal government.

This statute is Congress’s last word on the subject. But Article II is the final word on the subject.

So I’ll say there’s a lot to say about that. I don’t I hope I don’t think that scenario is going to happen. I hope it doesn’t happen.

But here’s what I would here’s what I would say about it. One is this is kind of the powers that Lincoln claimed in the Civil War, which was obviously a completely different situation than anything we’ve seen to date in this country. So, you know, there are a bunch of Lincoln Civil War precedents in about presidential action, but the circumstances there were so completely different that I don’t think they would be pertinent.

So but setting that aside, basically, here’s how I see the law. I mean, the president’s Article II power to use the military and the domestic sphere such as it is is the protective power. And this is the power, as we’ve discussed, to use the military in the domestic sphere to protect the property personnel and operations of the government in a protective short of law enforcement capacity.

As we’ve discussed, this is a longstanding executive branch practice and understanding. It has not ever been it has not ever been blessed and blessed in those terms by the Supreme Court. So it seems to me that even using the troops in a protective function is something that would be subject to full judicial review.

And maybe, you know, we’ll see. I mean, it’s a novel interpretation. It’s not a novel interpretation.

It’s a stretchy interpretation of a case called In re Neagle that the court has never passed on. But beyond that, I think you’re talking about something even more aggressive than that.

You’re talking about something like martial law, which is basically the replacement of military rule for civilian rule. And I don’t believe I mean, just staying within the four corners of the law, I don’t believe the president has the authority to unilaterally impose martial law in the sense I just described it. There’s no canonical definition of that.

But in the sense of replacing military for civilian rule, basically that would entail going further and spinning the red of habeas corpus, whicah, again, Lincoln claimed he had authority, the authority under Article two that the president had the authority to suspend the writ. I think the better understanding and the clearer understanding now is that that’s a power under Article one, section nine that clearly lies with Congress, even though it’s written in the passive voice. So I don’t believe that the president could successfully suspend the writ of habeas corpus, although I’ve written about this.

They threatened it. I mean, Stephen Miller came out six, eight months ago and said, we’re thinking about spending the writ. He was ambiguous.

I thought he was just gaslighting. It seems like he was at the time. So I don’t think that gamut can work.

I don’t think there’s any legal route for the president to be able to do that under anything like current conditions or really at all absent something like the Civil War situation, which doesn’t mean they won’t try it. I just think that they’ll have serious resistance in the courts. But that just begs the question about whether, you know, if we’re in that kind of extreme scenario.

And again, I don’t think we’re going to be there. If we’re in that kind of extreme scenario, it’s not clear what role the courts will be playing.

Well, I think we we probably conclude by saying the in this latest saga with the threat to invoke the Insurrection Act, it turns out that, you know, as bad as the statute is, as much discretion as it seems to afford, there are a whole host of issues facing the administration attempting to invoke it and the circumstances as we currently think about it. And we’re about to we’re about to learn a lot about the constitutional guardrails against various presidential assertions of authority in a number of contexts, including these elections that are coming up. Let’s hope not. But that may be the case.

It may be the case. We’ll see. Thanks, Bob.

Thank you, Jack.