Bob and Jack discuss the Trump administration’s indictment of former FBI Director James Comey, the lawfulness of the Lindsey Halligan appointment as interim U.S. Attorney, the implications of Trump’s full takeover and weaponization of DOJ, and how to think about reform in this context.

Thumbnail: Interim U.S. Attorney Lindsey Halligan, then Senior Associate White House Staff Secretary, with Chief of Staff Susie Wiles, at White House Event to Celebrate Women’s History Month (White House Photo).

This is an edited transcript of an episode of “Executive Functions Chat.” You can listen to the full conversation by following or subscribing to the show on Substack, Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts

Jack Goldsmith: Good evening, Bob.

Bob Bauer: Good evening, Jack.

It’s Sunday night, and we’re going to talk about the Trump administration’s indictment of former FBI Director James Comey last Thursday on two counts, one for false statements to Congress and the second for obstruction of a congressional proceeding. The main charge, such as it is, is in the first count, false statements to Congress. Basically, and I’m paraphrasing from the indictment, it doesn’t say much.

It says that on or about Sept. 30, Comey “willfully and knowingly” made false statements within the jurisdiction of the legislative branch of the government by falsely stating to a U.S. senator during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that he, Comey, had not “‘authorized someone else at the FBI to be an anonymous source in news reports’ regarding an FBI investigation” concerning “PERSON 1.” This statement was false because, as Comey then and there knew, he in fact had authorized Person Three, unnamed, to serve as an anonymous source in news reports regarding an FBI investigation concerning Person One. That is one of the briefest, maybe the briefest, indictments—there’s a little paragraph on the second page—that I’ve ever seen.

It doesn’t tell us anything. There’s been massive speculation about what Comey might have done, might be accused of, and the truth is we don’t know yet.

Let me just start off, before we get to the substance, by saying that there’s a serious question whether Lindsey Halligan, the interim U.S. attorney, was legally appointed. If she wasn’t legally appointed, then I think the indictment will be invalidated and thrown out, and the statute of limitations runs Tuesday.

Ed Whelan made the case for this on his Bench Memos blog. Basically, Title 28 U.S. Code 546 authorizes the attorney general to appoint an interim U.S. attorney, and the statute basically says that appointment can go for 120 days, and then after that, the district court gets to appoint the U.S. attorney. The Justice Department has long interpreted this provision to mean that the attorney general gets one 120-day appointment, and then it falls to the judges. There’s an opinion by then-OLC Deputy Sam Alito to that effect, an old opinion that was actually recently published.

So under the long-standing DOJ view, there had already been a 120-day appointment for Eric Siebert. DOJ didn’t even have the authority under the statute to appoint Lindsey Halligan, the president’s former attorney, as the interim U.S. attorney at EDVA. So there’s a very good chance the case just stops right there on a jurisdictional or authority ground. But I just mention that to get us started. Maybe we should turn to the substance. What do you make of the substance of the indictment? What might it involve?

You pointed out right at the outset, there’s a question about whether or not the U.S. attorney who took the case to the grand jury and ultimately secured the indictment on two counts, a third the grand jury refused to return. But that’s part of a very long and complicated story here. As you pointed out, she’s a former personal attorney of the president.

He installed her after pushing out the prior U.S. attorney, a U.S. attorney that had been appointed by his administration. And by all accounts, in the press reports, he pushed him out or directed that he be pushed out because he had doubts about this case. He had doubts about the merits of this case.

So out he went, and then he was replaced by a former personal attorney of the president’s, who is not only an insurance lawyer by training and trade, but has never had any experience bringing criminal prosecutions. You take that together with the cryptic, highly abbreviated character of these indictments that have given rise to all sorts of questions about what precisely the case is. Note, for example, that the precise statement that was alleged to be false isn’t even included in the indictment.

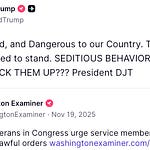

It’s not clear to many precisely what he might have been lying about. And then the president’s insistence that the case be brought, an insistence that was communicated to Pam Bondi, maybe originally a direct message, but that was then published to the world on Truth Social, and his celebration of the case after it was brought, the celebration of the indictments after they were brought. So this, I can’t remember anything like this. I mean, this is absolutely extraordinary, and it’s been treated as such by commentators, at least many commentators, and certainly even some on the right, if you will.

Yeah. So let’s just, I agree with that. And it’s really salient, it seems to me, that Bondi and the deputy attorney general Blanche sided with the then, I guess he was the interim U.S. attorney, in thinking the prosecution shouldn’t be brought, and it was overruled by the president. So that’s a remarkable thing by itself. It must have been an extraordinarily weak case for Bondi and Blanche, knowing that the president wanted this to happen, to think that it shouldn’t be brought. And I think that speaks volumes about the nature of the prosecution.

The thing, just to underscore if it’s not obvious, is this is the president of the United States willfully ordering the Department of Justice, and through dismissals and appointments and threats, implicit threats at least, to the attorney general, making sure that this prosecution, this indictment is able to be brought against Comey. It’s the total takeover by the president of the Department of Justice. It is, from an Article II perspective, probably just fine.

I mean, in the sense that the president of the United States, it was clear in my view before Trump v. the United States, and it was really clear afterwards, that the president of the United States, when you strip away the norms and you just look at the law, has the authority to direct prosecutions and to dismiss people who won’t follow his orders. I think that’s all technically allowed by Article II. But if you just set that aside for a second, what you have is the Department of Justice now openly, under the full will of the president, bringing a dodgy indictment against one of his professed enemies. What do you make of that? I mean, what world are we in in which that’s going on?

I think for all the criticisms that each party has occasionally had of the way the other has run the Department of Justice, I think what’s going on here is an extraordinarily transparent weaponization of the Department of Justice. By the way, in comments that he made after the indictment was brought, in Oval Office remarks, he made it clear it doesn’t stop here.

There have been press reports of other targets of his political ire that he is ordering up investigations of, including philanthropies that he believes have been funding what he would characterize publicly as radical left dangerous causes, but also ex-presidents and members of Democratic administrations before his administration, Trump 2.0, or even Trump 1.0, took office.

Let me say one thing about the message to the attorney general Bondi. It’s hard to describe how extraordinary that message is. Here you have a real-time directive to the attorney general of the United States. When I say real time, not retrieved from the archives years later, or recorded in a memoir by a former administration official, but a real-time directive to bring the case.

He argues that he didn’t trust the U.S. attorney previously put in place, Erik Siebert, because Democratic senators had returned blue slips, had approved the nomination. They didn’t have an objection to it. That, per se, he found very troubling.

Didn’t the president nominate him to be the actual U.S. attorney?

That’s correct. That is correct.

He kept that out of the Truth Social posting, that he had nominated him for confirmation.

Correct. That was his choice. Then he learned or he understood that Democratic senators had no objection. That, per se, was objectionable to him. Then he went on to say, listen, I was terribly mistreated. I was prosecuted and impeached several times.

Basically, turnabout fair play. My reputation is being damaged by the failure of my administration. We could talk about who he thought it was being damaged with by failing to bring this case.

This is really quite remarkable. We’ve never had that kind of real-time documentation that I’m aware of, of the president speaking directly in what I assumed he thought was a private communication with his own attorney general to bring a case like this.

Except it was on Truth Social. A lot of people interpreted that as a mistake, but it was on Truth Social. I just want to briefly lay out what dim checks there are on this.

Let’s just imagine. The president clearly—I take it that we’re going to talk about how much he’s already succeeded in his vendetta against Comey by securing the indictment. It’s clear that the president will overwhelm all career official resistance within the department. That was the message when he got rid of Siebert and put Halligan in place. If it’s not Halligan, they’ll do it better the next time and make sure the t’s are crossed and the i’s are dotted. It’s clear that the attorney general and the deputy attorney general will get in line.

But then there’s a question about who’s actually going to run the case, run these cases. Halligan is clearly unqualified to do so. She could barely secure the indictment. There was an embarrassing transcript that was released with her colloquy with the magistrate in which she clearly didn’t know what she was doing. They’re going to have to, if they want to continue down this path and really be aggressive, they’re going to have to find attorneys that can confidently bring these indictments. It’s traditionally very easy for a competent prosecutor to get a secure indictment from a grand jury.

We’ve seen in this case, the grand jury didn’t return the indictment on the third count. It was close on the first two counts. The grand jury was maybe a dim check here, but not much. But we’ve seen in the District of Columbia, grand juries turning away, I think it’s five or six indictments already, which is an extraordinary number. It remains to be seen what, if any, check the grand jury will be. I’m not suggesting it’s a robust one, but it’s a potential one.

That’s a check that, at least in theory, is not under the control of the unitary executive. Then the next level of check is the law before the judge and the jury. I think Robert Jackson said in his famous speech to prosecutors that if the federal, this was 70 years ago or whatever, if the federal government goes after you with all it’s got, it can find a crime. I’m afraid that’s what we’re going to be seeing. I think it’s not going to be limited to what they did in the political realm. We’ve already seen this with the use of the housing agency to go after people for other ends. It’s not clear. What do you see as the checks here, if any? Will the judiciary, including the grand jury and trial jury system, be a check on this? How do you see it?

I think the grand jury, which a system, as you’ve pointed out, is not a reliable check against prosecutorial overreach because of the way the grand jury system is structured. Prosecutors have enormous sway over grand juries. As you point out, typically prosecutors with a minimum degree of competence can get the indictments that they want.

There are exceptions. You’ve noted a few recently in the District of Columbia, but I do think those all are relatively extraordinary. It depends jurisdiction by jurisdiction, case by case. It can happen, but it doesn’t happen routinely. I worry about that a lot.

I have obviously given some thought, because I posted it recently on our site, about what we might do to shore up protections for targets in grand jury proceedings.

I want to come back to that at the end. We should wrap up with that. What do you think about the other checks?

I really do think, and I know these are very difficult cases to bring, but I think this is going to be a case that’s going to test on these extraordinary facts a selective or vindictive prosecution case that a court is going to have to evaluate. We know what we know because of the remarkable—I don’t think it was intended as such—transparency of communications within the administration and leaks to the press on this topic, and the resignation of Eric Siebert, and the president’s intention to direct Bondi, probably originally in a direct message, but then it showed up on Truth Social.

But there may be discovery on that issue, and who knows what that would produce. Nothing in the reporting suggests it will be at all a pretty picture. The courts are going to have, in these extraordinary circumstances, an important policing role to play, and we’ll see just how well they play it.

I also think that if the president attempts to do what he suggested, which is to comprehensively target former political enemies, whether they’re organizations or former public officials, we will see just how much of a check in these unprecedentedly weaponized circumstances grand juries can be, even in their current unreformed state.

But first order of business, let’s see what the court says in the early going about the sufficiency or the validity of these indictments.

Let me speculate about what the president is thinking and what might happen here. I’m not so sure. I think that maybe that first Truth Social message may or may not have been an accident, but Trump never hides his exercise of power and his kind of takeover of institutions. I think he likes to display, and he’s written about this, how he likes to display and gets benefit out of displaying his control over these institutions. Also, when you are willful and just kind of overriding the norms and just flaunting them openly, that’s much more effective in destroying the norms. So I think that the overt power moves he’s making is it could be...

It may have been an accident, but I think that typically he doesn’t hide these things. I wonder what you think about whether... I think there’s a decent chance, as other people have said, that this case gets, if the motions are made, and I think they will be made, gets dismissed early on long before it gets to trial. Maybe on the appointment issue, maybe on selective or vindictive prosecution. I think that’s going to be very hard, but maybe. Maybe on just inadequacy of the indictment, or maybe it’s just that the indictment fails as a matter of law.

If that happens, it’s a Biden-appointed judge, a respected judge, a Biden-appointed judge. If that trial judge dismisses the case before it gets to trial, at that point, is Donald Trump happy there? Because certainly what’s going to happen then is he’s going to go after the judge. He’s going to continue ratcheting it up. Do you think Trump is thrilled with the indictment and that’s all he wants, and he’d be happy with that if the case is dismissed? Or what happens if the case is dismissed?

Certainly in the short term, first of all, when the indictment was secured, he celebrated it. And no doubt he was happy that he could deliver to the base, if you will. Recall that in that message to Bondi, he said, it’s killing my reputation. I think it’s with his base that he thought his reputation was being harmed. So he got satisfaction on that score.

And he will, of course, attack the judge if the case is dismissed, no question. But on the other hand—and by the way, this is more of a prayer than a prediction—if he is smacked down in a case that he was told by his own attorney general and deputy attorney general should not have been brought, it may slow him down in his desire to repeat this performance with other enemies of his who he’s already publicly identified and singled out for potential attack.

So he will make no doubt a bluster. He’s never wrong. He’ll never confess that he was wrong or that the case was weak. But he may take a step back because there are only so many of these that he’s going to want to lose, and some of them will not be brought before a judge appointed by President Biden.

Let me make one other comment about his public statements. You’re right that he makes a show of power and what it is that he thinks he can do. But he also, in this instance, kept on reminding himself that he had to periodically say that the case was a good case. He didn’t give any reason, and nobody’s trusting his legal judgment on that. And I think his motives are pretty plain. But at one point, you know, he said it was a great case. So, you know, every now and then, you know, he kind of remembers vaguely that perhaps he’s overstepping himself a little bit—or frankly a lot. But I don’t think that’s going to confuse anybody about what was really going on here.

Yeah. So I don’t think it’s fruitful, unless you want to, to talk about what the actual allegations might be. Some people have suggested what he’s accused of lying about. Does it have to do with whether he authorized the Deputy FBI Director McCabe to leak or whether it was because he directed Professor Danny Richmond to leak something? Did his statements before Congress constitute a lie with regard to either set of facts I’m doubtful about that, but we really don’t even there seems to be uncertainty because the indictment is so thin about what the indictment is even about. My sense is that they’re still scrambling around trying to figure out what the indictment is about in the government.

So I don’t know if you want to comment on that at all before I asked you about some wrap up questions about reform.

No, I would only say, I mean, it’s remarkable the indictment after all this hoopla was secured and now there’s a disagreement about what precisely it refers to. Nobody’s quite sure what the crime was that is being charged here. And we’ve seen commentary on that in a number of places, that the sheer impossibility of discerning what is being charged, again, and we should stress this, under law that makes it very difficult to bring these kinds of cases.

The degree of intentionality, the clarity with which the false statement is delivered do make these cases hard to bring and the way—

Hard to succeed on.

Yes, precisely. Hard to succeed with, not necessarily hard to bring if you don’t care about success.

Yeah.

But I think that all of that, together with all the other extraordinary circumstances here, does not suggest very strongly that this case doesn’t have a long shelf life.

Okay. Let’s talk about the piece you wrote last week in connection with, I think, anticipating these indictments about reform. You and I wrote a book about the need for reform of the presidency after Trump 1.0. We’re now in an entirely different universe of presidential behavior in Trump 2.0. And so why don’t you talk about what you said about how to think about reform in this context?

And how do you think about, maybe if you can comment on it, how do you think about reform generally? I mean, we’re in eight months into the second Trump administration with the Republicans in charge of both houses of Congress. It doesn’t seem like reform is in the offing anytime soon. But is now the time to be thinking about it nonetheless? And what did you propose in this context?

I think, and I think you and I thought when we wrote the book, it’s never too early, particularly because of the very long lead time required for effective reform and the difficulty of ever even achieving a large percentage of necessary reforms. It’s never too early to discuss it and to see whether you can develop a bipartisan consensus because fully weaponized federal law enforcement is not a winning proposition for either political party. I mean, I don’t see how anything could be more obvious.

If the Republicans can do it, the Democrats can do it back. And in fact, the Republicans today, if you will, in the hardcore pro-Trump mongering of the party who think he’s justified in doing this to Democrats because they believe Democrats did that to him. This is a downward spiral that can go nowhere good. In fact, it heads in a disastrous direction.

So for that reason, I do think it’s not too early to look at reforms. And I mentioned a few. And by the way, sometimes they can’t be silver bullet, you know, comprehensive, immediately effective reforms. But one example would be, and there have been many proposals by experts, and I’m not an expert, to shore up the protections of targets and grand juries. Grand juries are very much under the sway of prosecutors, as we discussed earlier.

There are ways to strengthen the protections for those who are targeted before a grand jury by a government. There are important steps the courts could take in this case to create precedent on selective prosecution as hard as those issues can be. And then I also think there’s an enormously significant civil society role here.

There needs to be a full-on bipartisan stance that this is not how federal law enforcement can be managed. And there are various ways to do this, some of which break through gridlock at the national level and permit that kind of consensus to develop at the state and local level. So we have a controversial American Bar Association that’s continuously under attack.

There are lawyers in communities around the country who are highly regarded, Democrats as well as Republicans and independents to boot, who understand that this is a real threat to the rule of law. So within the profession and elsewhere in community leadership organizations, there needs to be clarity that this is not the way the American legal system can go.

Yeah. Okay. I mean, I agree with you on the grand jury reform.

If you’re talking about limiting the prosecutor’s powers, maybe allowing the defendant to show up and say more before the grand jury, whatever they are, is this a proposal not just in these presidential retribution cases, but across the board? That’s a major change in law enforcement across the board.

So that would be, and maybe it’s justified by what we’re witnessing. And the other thing I would say is, even if there are conservatives around the country who support this, and I’m confident that there are lots of conservatives in the Congress and even in the administration who worry about what’s going to happen when the Democrats exercise this power. There’s nobody, I haven’t seen anyone in Congress really, has there been to say, this is a terrible thing, we ought not be doing this.

So it just seems like we’re very far from the kind of bipartisan, and I don’t think you disagree. I’m just trying to explain where we are. Very far from having any sort of bipartisan buy-in on this particular point.

Now, maybe after we’ve suffered through this and maybe after another round, it’s not clear when the light bulb will go on in both parties. But I just don’t, we’re not close yet, I think. And I don’t think you disagree.

Yeah, and I don’t know how to measure closeness, but I agree, it’s not a tomorrow thing. But as you pointed out, we’re eight months only into this administration. And so this full weaponization program is really ripening now for the first time, or the results of it are becoming more starkly clear now than would have been the case three, four, or five months ago.

So it may be that the normal painstaking effort that is required to assemble these kinds of coalitions will be expedited or can accelerate under these extraordinary pressures.

All right. Why don’t we stop there? Thanks very much.

Thank you.