Presidential Bad Faith in the Law of Emergency Power

Trump’s false claims about Portland matter a great deal in evaluating the legal basis for a military deployment in Portland—and in other cities.

Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup—brief daily summaries of news developments and commentary related to executive power.

The Oregon National Guard case pressure-tests the courts in their response to this presidency. They do not have a rich range of resources on which to draw in deterring the breadth of executive discretion in federalizing the National Guard under the relevant statute, 10 U.S.C. §12406. This law does not define terms; it is short and raises more questions than it answers. The case law is spare, and the relevance of key precedent is contestable. Not contestable are the president’s demonstrably false claims about the basis for calling up the Guard for deployment to Oregon, and yet the lawyers before the courts are more scrupulous in their formal legal presentations. It is a challenge for the courts, but much rides on their getting right the question whether, as presidential aide Stephen Miller asserts, the president can claim “plenary authority” under the statute to deploy troops to the homeland as he chooses.

In these terms, this is a hard case. But I do not see it as a close one. Judge Karin Immergut’s opinion is well reasoned, and it meets the key test: It reads the law in a way that ensures meaningful judicial review of presidential deployment of the military in the homeland, but it does not 1) position the courts to routinely second-guess executive exercises of discretion, or 2) substitute its judgment for Congress’s in re-writing a statute that confers this discretion. That is not an easy task. But she shows that the case for her conclusion is strong, and not especially close, by putting, front and center, evidence of presidential bad faith.

I am addressing here only selected issues raised by the case and various assessments of the Immergut opinion—I will write more on others after we hear from the Ninth Circuit—but these seem to be key in the current debate. I am guided largely in the choice of those issues by the points of discussion (and disagreements) with Jack in our video chat and his post yesterday.

The Statute

The statute in question authorizes the president in all of 132 words to call up the Guard to address invasion, rebellion and the inability to “execute the law” with regular forces. Not a single term is defined. One could say that the absence of definition merely underscores the breadth of discretion Congress chose to authorize. But this is a statute, and when there is a question of what it means in particular circumstances, the courts are called upon to apply it to the facts at hand.

A major question is what, keeping to its judicial function, a court can appropriately do.

One step that Judge Immergut takes is rejecting the administration’s attempt to conflate two bases of authority under the statute—thereby utterly misreading its text. The government claims that “rebellion” has occurred if there is any “direct” inhibition of the execution of the law. This is a remarkable argument, and it is defective on two counts. First, this reading of the statute rewrites it, collapsing two sections of the law into one. Second, it opens the way for the government to treat as insurrectionists any individuals engaged in conduct of any kind that is normally handled as a standard law enforcement issue. Judge Immergut does here what courts do, ruling on a straightforward, important question of statutory interpretation.

But the court also rightly, in my view, considers the wider consequences of a boundless treatment of the president’s discretion, establishing a critical measure of accountability, on judicial review, for its good faith exercise. As the court recognizes, there must be a limit—a case or category of cases in which the president may be found to have abused the discretion provided for under the statute.

Consider the not entirely speculative hypothetical case where the president argues that cities with “radical, lunatic left” Democratic mayors (aided and abetted by radical, lunatic left governors) cannot enforce the law, because radical left lunatics are basically anarchic, animated by “Antifa” impulses. Hence, on that justification, he calls up National Guard troops to all such cities. Perhaps some might argue that the discretion provided for under Section 12406 extends that far. That Congress intended an authorization so broad is highly implausible.

The Case Law

There is not much. But before turning to the “good faith” standard adopted by the Ninth Circuit, in reliance on Sterling v. Constantin and followed by Judge Immergut, some word about two other cases, Martin v. Mott and Luther v. Borden is in order. Each—one decided in 1827 and the other in 1859–have broad language about presidential power under analogous law to determine the existence of emergencies that justify calling the military into service. In Mott, in a frequently cited passage, the Court stated that “that the authority to decide whether the exigency has arisen belongs exclusively to the President, and… his decision is conclusive upon all other persons.” But the power of this precedent—and the language the Court uses—has to be evaluated in context, on the facts before the justices. Mott was a challenge to military service in wartime by a citizen who was called up and refused to serve. Luther v. Borden involved an armed, honest-to-goodness insurrection against the charter government of Rhode Island, and it is notable that the U.S. Government threatened to deploy military forces but didn’t. Neither case is at all like the presidential deployment at issue in Oregon.

And it bears further notice that the Luther Court, recognizing the danger of the abuse of broad discretion, took comfort in “the high responsibility [the president] could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment…furnish[ing] as strong safeguards against a wilful abuse of power as human prudence and foresight could well provide.” This connects directly to the question of “good faith” on which Sterling v. Constantin, decided in 1932, turns. There, the Court, as read by the Ninth Circuit, established a standard for construing discretion that looks to whether its exercise was “conceived in good faith,” with a colorable basis in fact within a “permitted range of honest judgment.” Jack suggests that the Ninth Circuit may have misread Sterling: that its discussion of “‘good faith’”…concerned not the exigency triggering the statute but the ‘measures to be taken in meeting force with force’.”

Jack raises an interesting question. I agree that Sterling is not a model of clarity on this point, and there is one plausible reading that puts the most weight on the breadth of executive discretion, as in the Court’s statement that “Fundamentally, the question here is not of the power of the Governor to proclaim that a state of insurrection, or of tumult, or riot, or breach of the peace exists and that it is necessary to call military force to the aid of the civil power.”

But there is language that goes the other way, as does (in my view) the entire thrust of the opinion, which is why I see the Ninth Circuit as having correctly understood the case. The Sterling Court did not make a clear distinction between the declaration of emergency and specific “measures” to be taken in addressing it. The governor of Texas proclaimed an emergency justifying the deployment of military force because it sought to enforce statutory limits on oil production at certain wells and was failing to achieve this objective through the ordinary judicial process. That was the emergency—and, significantly, the Court cited an earlier case, Mitchell v. Harmony, for the proposition that an “emergency must be shown to exist (emphasis added).” The Court also affirmed, as “fully supported by the evidence,” the District Court’s findings of fact that “not only was there never any actual riot, tumult, or insurrection which would create a state of war existing in the field, but that, if all of the conditions had come to pass, they would have resulted merely in breaches of the peace, to be suppressed by the militia as a civil force, and not at all in a condition constituting, or even remotely resembling, a state of war.”

This seems enough to support the Ninth Circuit’s conclusion from Sterling that an executive is bound by “good faith” and “honest judgment” in the determination that the authorities conferred by §12406 have been triggered. Context also matters, and the Court was, in fact, addressing a case of executive bad faith.

And it is very hard to see, if there is to be judicial review at all, how it would not be conducted precisely with attention to bad faith. Outside this concern, there are difficulties facing the courts in judging the conditions of emergency: This is an executive function for which the courts lack the capacity, not to mention constitutional warrant, to second-guess presidential determinations. But Jack then asks how this “good faith” standard could be operationalized “if the government otherwise presents facts in court showing that the statutory standard was met.” I offer the following answer.

The Judiciary, the Facts and the Relevance of “Bad Faith”

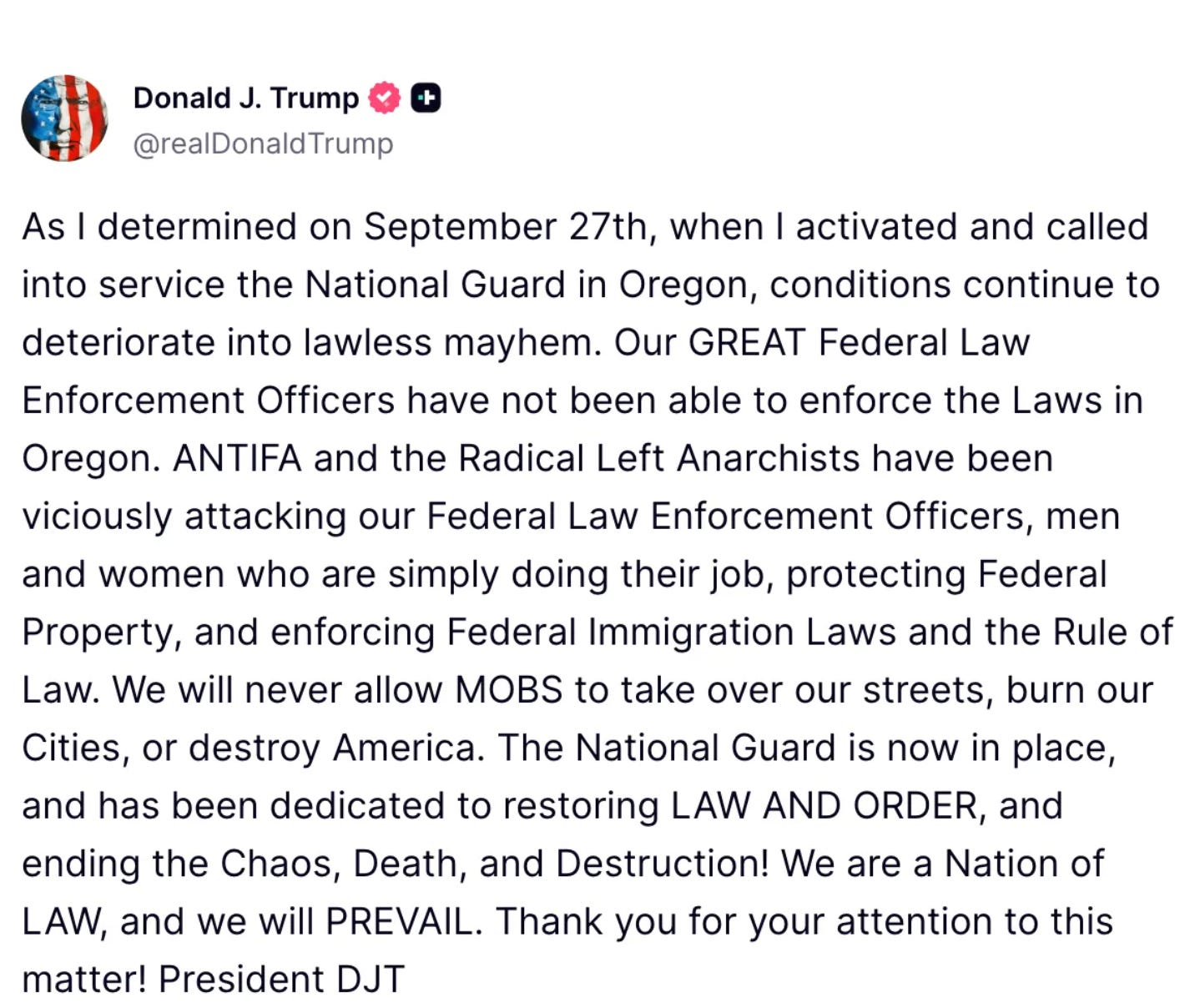

In my chat with Jack, I argued that the Court did show how the “good faith” standard could be operationalized in considering the president’s false statements, one after the other, about the situation in Portland. There is no question the judge was correct in her conclusion that Trump’s claims on Truth Social about a burning, war-ravaged Portland, a scene of “Chaos, Death, and Destruction,” are “untethered from the facts.” But are these presidential statements relevant?

As one of the Executive Functions readers who watched the video subsequently pointed out to me, the U.S. government conceded this relevance. As Judge Immergut noted, one of the affidavits the government submitted, by the Acting Vice Chief of the National Guard Bureau, characterized the President’s Truth Social posting of October 1 as “further explain[ing]” his directive to the Defense Secretary on September 27. This was not a concession under pressure or questioning from the court: It was affirmatively submitted to the court as part of the record of the president’s determination under §12406.

And it stands to reason that it should have been so considered. A president—certainly this president—may say all sorts of things all the time, and not all of it is charged with actual or potential legal relevance. But when a president speaks to the nation on a matter of great moment, such as the declaration of an emergency on the basis of which he federalizes the National Guard in the homeland, it is difficult to see how these statements or speeches lack relevance. It should not make a difference whether the president chooses social media, an Oval Office address, or the Rose Garden as the venues for these statements. That his lawyers show up in court with different or more carefully drawn submissions only further supports an inquiry into bad faith. What the president has to say about his reasons in these circumstances should, it seems, carry great, if not decisive, weight. The judiciary is not there to be made a fool, asked to shield its eyes and cup its ears, ignoring the president while attending only to what his subordinates say in court.

Taking account of these statements does not invite a standard of open-ended inquiry into presidential motive in all conceivable circumstances in which the president seeks to exercise emergency authority. To the contrary, it separates the more extreme case—where the president’s actions fall beyond the limits of lawful discretion—from ones where the court might routinely and questionably second-guess the factual basis of the president’s determination.

In my video chat with Jack, we discussed my view that the president’s statements outside the pleadings should influence the court in its assessment of the facts on the ground, and I gave my reasons why it should. In a specific hypothetical we discussed, where a case on the competing factual submissions “barely” crosses the line to meet the requirements of the statute, I argued that the president’s false claims would weigh against the credibility of the government’s formal position and cost the government a ruling in its favor.

Following the video chat, an experienced trial lawyer wrote to me to stress that this credibility determination is not at all unusual at the temporary restraining order stage of a proceeding, when the facts are presented through the competing affidavits, the testimony is not subject to cross-examination, and credibility may be the decisive factor. This was the approach Judge Immergut took. She reviewed the competing factual submissions and, in this exceptional case, where the president’s repeated factual claims for ordering deployment under §12406 was manifestly false, she made an unavoidable finding of credibility— “bad faith” and the absence of “honest judgment.” In my view, she admirably showed how the Sterling rule could be put to good effect consistent with the judicial function.

It also did not help the government to get over the credibility barrier by pointing to unrest and violence in other parts of the country or positing the potential that conditions could worsen in Portland. These arguments merely take the case even farther away from the facts on the ground in the relevant locality—the one where the emergency conditions have purportedly arisen. When the good faith of the president’s actions is necessarily questioned, undermining the government’s factual submissions to the court, the more attenuated claims it might make are rightly discounted. This same discount applies to a generalized allegation that assistance provided by out-of-state federal law enforcement demonstrated the government was unable to enforce the law in Oregon with regular forces. This, Judge Immergut noted quite reasonably, is “a routine aspect of law enforcement activity”: “If the President could equate diversion of federal resources with his inability to execute federal law, then the President could send military troops virtually anywhere at any time.” Were there no clear, pervasive evidence of bad faith, this array of backstop arguments might have carried more weight.

Conclusion

There is much more to say, of course, about presidential uses and abuses of emergency authorities, and the other sources of authority, such as the Insurrection Act, that the president has threatened to invoke. In the days and weeks ahead, Judge Immergut’s strong opinion may influence the course of appellate review. There is also a case to be made that her analysis could affect what the president might hope to achieve by turning to the Insurrection Act—and not to his liking. But that is for another post.