The New Phase in President Trump’s Midterm Maneuvers

Pressuring Senate Republicans to clear the way for a law the House GOP is preparing to change voting rules

Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup—brief daily summaries of news developments and commentary related to executive power.

Donald Trump’s strategy for addressing what he insists is a rigged electorate system is shifting to a new phase. His party in Congress is preparing legislation to fulfill key objectives laid out in his executive order issued last March, including new protections against alleged widespread noncitizen voting, an end to the dangers of mail in balloting, and replacing machine voting with hand counts. In the immediate aftermath of this year’s elections, Trump convened Republican senators to make his case for ending the filibuster, emphasizing election law reforms as a legislative priority that could be achieved through this proposed rule change. He told the lawmakers, “We should pass all the things that we want to pass, make our elections secure and safe,” citing the termination of mail voting and new voter identification requirements. Since then, Trump has pressed this case, posting on Truth Social: “TERMINATE THE FILIBUSTER!”

In the House, the Chair of the House Administration Committee, which has jurisdiction over election law matters, has stated that preparation of the election law legislation the president favors is underway, and he expressed confidence that a coalition could be assembled to pass it. Trump’s concern is that if the House does act, the Senate may not—because of the filibuster.

So far, Trump lacks enough Republicans votes in the Senate to end the filibuster. But the situation remains unsettled, as some reporting indicates that his appeals have not been entirely without effect. It raises the longstanding problem of political reform. A congressional majority that pushes reforms of this kind over fierce opposition party objections invites the suspicion or accusation that it is motivated more by partisan self-interest than sound public policy. The filibuster operates as one defense against partisan power plays, and both parties have an interest in keeping it in place. They are divided on much but united at least in their suspicion of the other, especially the belief that what travels under the banner of reform is typically consistent with—if it is not entirely motivated by—what is most advantageous for the reform advocates’ electoral strategies. Reforms may pass over opposition, but the losers in that battle live to fight another day, to undo as soon as possible what has been done and to launch reform initiatives more to their liking.

There is recent history to suggest that Senate Republicans would be very sensitive to these problems. In 2021, House Democrats sought to pass a large package of election and other political reforms, known as H.R. 1. Republicans vehemently opposed it. They objected to these reforms on policy grounds, but also because, as they saw it, the Democrats were abusing their majority to force changes in the law to their own political advantage. In the words of Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell, the Democrats were seeking to alter voting and campaign finance rules so that they could “win elections in perpetuity.”

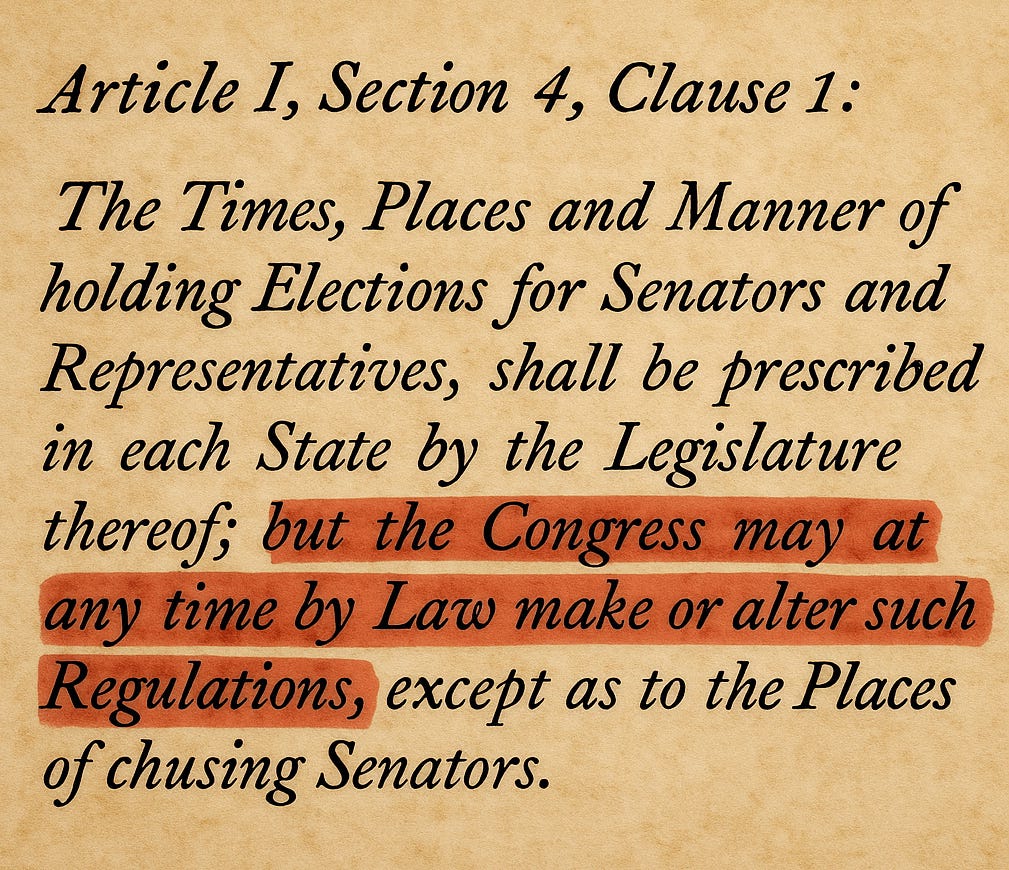

Republicans also criticized the attempt to bring Congress into an active role in setting election laws. As a constitutional matter, under Article I, Section 4, Clause I, Congress may legislate changes in the rules governing the “Times, Places and Manner” governing the conduct of federal elections. Normally, it does not. The responsibility falls primarily to the states in the highly decentralized system for conducting elections that we have in this country. Republicans have been most committed to robust federalism in this area of lawmaking. In the case of H.R. 1, House Republicans denounced the bill as “nationalizing our elections,” and on the Senate side, McConnell claimed that “this is really about is an effort for the federal government to take over the way we conduct elections in this country.”

The House passed H.R. 1, but the Senate did not, as sponsors could not muster enough votes to overcome a filibuster. This struggle is on the verge of being replayed, but with the two parties reversing positions on congressional intervention in the process by which voting rules are established or reformed. Now Democrats have occasion and every reason to allege a “power grab,” and the partisan temperature is all the higher in these circumstances where Trump insists that Democrats can only win if they cheat and that the measures he is calling for would pave the way for Republican electoral success. It is more typical for calls for election law reform to be framed as serving the public interest, rather than, as Trump has done, placing the partisan stakes front and center—the advantages for one party and disadvantages for the other.

Trump feels compelled to turn to legislation because the more direct, unilateral route he has first attempted—an executive order—is rife with legal problems. One court has already issued a permanent injunction against implementation of one provision of that order that seeks to impose a new “proof of citizenship” requirement. More generally, the court stressed that “the Constitution… leave[s] election regulation solely to the States and to Congress.” Trump previously pledged that another executive order, by which mail balloting and machine voting would both be ended, would be forthcoming shortly, and he may still issue it. But his lawyers would have advised him, one assumes, that his prospects of making his desired changes by executive fiat are slim. A legislative fix is cleanest and, depending on how the changes are crafted, stands a better change of withstanding legal challenges.

The filibuster rules have been challenged and amended in a number of its applications. It no longer operates to require a supermajority to approve executive branch and federal judicial nominations, including nominations to the Supreme Court. It remains in place only for legislation. In arguing for doing away completely with the filibuster, Trump has chosen to highlight the path it would open for one party to change the rules for voting in federal elections. The reasons he has given for taking down the filibuster only served to underscore its role as a check in the case of election law reform against recurring cycles of hyper-partisan, winner-take-all politics. As presidents have no constitutional election rule-making authority, it should not be overly easy for them, in our system of separated parties, not powers, to work their will through his allies in the legislature.

It seems that both parties should be able to agree on that, and as recently as 2021, when the Republican filibuster blocked passage of H.R. 1, the Republicans were very much on the record on this issue. No doubt some Republicans will now argue, as Trump did in his remarks the day after the election, that Democrats will readily get rid of the filibusters when they return to power, if they deem this step to be in their interest. It is always easy for one party to make this claim against the other. But, in considering whether to go down this path, Republicans now under this pressure from Trump must ask themselves whether this is a sound prediction or simply a rationalization. And if the latter, where this will all end.