The Bad News in the D.C. Grand Jury’s Refusal to Indict Six Members of Congress

It did the right thing, but Trump’s targeting of members of Congress should prompt legal reform.

Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup—brief daily summaries of news developments and commentary related to executive power.

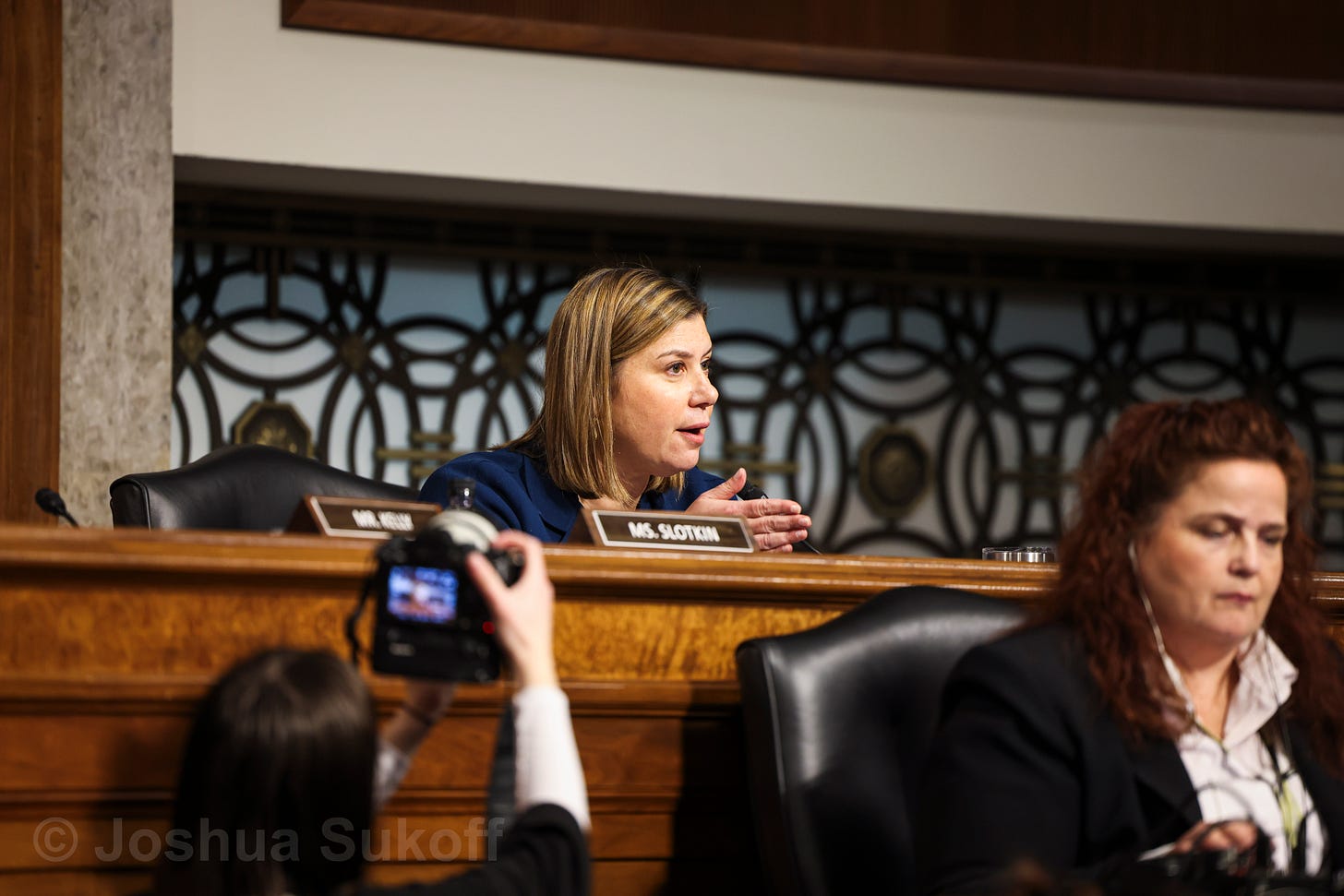

It is reassuring that a D.C. grand jury has reportedly rejected the administration’s attempt to indict six members of Congress for reminding members of the military that they cannot follow illegal orders. The charges the administration sought to bring lacked any credible basis. The Department of Justice sought to prosecute an accurate statement of law as an attempt to promote “insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty” in violation of a statute aimed at protecting service member morale. This groundless use of the statute was yet another example of the weaponization of law enforcement against the president’s perceived enemies. The grand jury, admirably, would have none of it.

That is the good news. The bad news—and it is very bad—is that the administration even attempted to bring such a case. A president who weaponizes the Justice Department against Congress has the means to undermine its critical (albeit too often suspended) checking function. The message to the legislators is that they cross the president at great personal risk. The mere threat of weaponization can affect members who have not been targeted but observe the targeting of their colleagues.

Donald Trump has already chosen to exercise the pardon power to reward reliable political support, and he has made no secret of that criterion for clemency in this administration. Now his government has moved from protecting favored Republican members of Congress from the consequences of criminal conviction to subjecting Democratic lawmakers to investigation and attempted indictment.

Courts will be called upon to adjudicate, case by case, claims of vindictive prosecution that arise in this context. This role of the judiciary (and of grand and petit juries) is critically important, but it goes only so far to address the problem. Relief from the courts may be slow enough in coming to satisfy this administration on the basis that—whatever the outcome of a particular investigation or prosecution—it has exacted a price that other members of Congress may be unwilling to pay. In this case involving the five members of Congress, the grand jury would not indict, but another jury, in a different case, might.

Is there a potential law reform that would help address the problem of a president bent on abusing executive federal law enforcement power to intimidate the Congress and undermine its independent performance of its constitutional functions? I think there may be.

A Law to Protect Congress from Weaponization

The reform would involve reviving, and completely revising for this purpose, the institution of a statutory special counsel. It would not, as in the case of the old independent counsel statute, serve to establish “independence” from the Department of Justice in the investigation and prosecution of the president, vice president, or other high-ranking executive branch officials. Its purpose would be flipped into the entirely different direction: Supplying a measure of protection against the executive’s misuse of prosecutorial power to intimidate or harass sitting members of Congress.

Under such a reform, if an administration is poised to investigate a member, the attorney general would be required to apply to a division of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit for the appointment of a special counsel. This eliminates the risk, evident in the case the D.C. grand jury has now rejected, that the Department of Justice just picks lawyers prepared to do the president’s bidding and brings cases without regard to law and fact for political purposes.

The court-appointed special counsel would have the authority to conduct the investigation with all the standard tools—subpoenas and the convening of grand juries. He or she would be required to follow standard Department of Justice policies and report to the attorney general. However, consistent with current Department of Justice regulations governing the appointment and duties of a special counsel, the special counsel would report to the Congress at the conclusion of the investigation on any specific investigative steps that the attorney general overruled.

In the wake of Trump v. United States, the attorney general would necessarily have the final say on declination or prosecution. However, in the event that the AG overruled the special counsel’s recommendation that prosecution be declined, the recommendation would be transmitted to the Congress along with the AG’s explanation for overriding it. Should the AG remain committed to prosecution, he or she could not be prevented by law from doing so. It would have to be left to the operation of ordinary-course politics to deter politically controversial prosecutions under this regime of modified prosecutorial independence and transparency. The goal would be to create disincentives to blatant politicization of the criminal justice system in one particular form—the targeting of lawmakers—which is especially dangerous to the constitutional order of separated powers.

Is This Constitutional?

One critical response to this reform is that the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. United States, affording the president either absolutely or qualified immunity for acts taken while in office, precludes any shared power with Congress over the conduct of criminal prosecutions. Those who might argue this position take the case to have effectively overruled the Court’s decision in Morrison v. Olson upholding the old independent counsel (IC) statute. While Morrison may have long before become “bad law,” Trump v. United States could be read to have clearly sounded, in Jack’s words, its “death knell.”

But in Trump v. United States, the Court did not overrule Morrison. It addressed the very specific question of whether a president could be prosecuted for actions taken while in office, and for that purpose, established immunities, including immunity when exercising “conclusive and preclusive” authority over criminal prosecutions. There are several reasons why its reasoning should not extend to a special counsel statute fashioned for the very different purposes than its predecessor.

First, the Court operated in Trump v. United States within the framework established by Justice Robert Jackson in his fabled Youngstown concurrence. It located the president’s “conclusive and preclusive” authority over prosecutions in his “exclusive constitutional power,” but it did not somehow read Congress out of the “zone of twilight” in which Congress and the president share some powers over criminal law enforcement. As the Court in Trump noted, “The reasons that justify the President’s absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for acts within the scope of his exclusive constitutional authority do not extend to conduct in areas where his authority is shared with Congress.”

Trump does not address or override the Morrison analysis of when Congress may provide the appointment of a federal law enforcement official as an “inferior officer” for purposes of the Appointments Clause. And Congress has also exercised the power to make temporary principal officer appointments in the criminal law enforcement sphere, which it does in authorizing district courts to appoint an interim U.S. Attorney when the president and Congress have failed to make a permanent appointment through the nomination and confirmation processes and the attorney general has exhausted the time limits on filling such vacancy.

And the Court’s reference to the pardon power as another “conclusive and preclusive” authority is also instructive. The Court, citing 1872 precedent, noted the absolute character of this power lies in its effect: “To the executive alone is intrusted the power of the pardon,” and Congress “cannot change the effect of such a pardon any more than the executive can change a law.” The pardon always operates as issued to relieve the pardonee of accountability under the criminal law. But, as Jack and I have written, “the current anti-bribery statute. . . would clearly apply to someone who offered a bribe to the president in exchange for a pardon,” and “there is a good argument that the anti-bribery statute also prohibits the president from offering or granting a pardon in exchange for a payment or something else ‘of value.’” The Office of Legal Counsel has concluded in the past that the bribery statute “raises no separation of powers questions were it to be applied to the President.” A pardon power that is “conclusive and preclusive” does not displace Congress’s place in shared powers over even this aspect of criminal law enforcement.

Second, citing Justice Jackson, the Court stressed that the novel questions presented by presidential immunity “may have profound consequences for the separation of powers and for the future of our Republic.” The focus, the Court stated, must be on the “enduring consequences upon the balanced power structure of our Republic.” A statute to address executive branch weaponization of the law against Congress, motivated by a concern with the “balanced power structure of our Republic,” seems to fit well within the Court’s constitutional concerns.

Finally, the specific issues raised by the executive’s prosecutions of members of Congress might lead the Court to reconsider the concerns considered in Morrison that applied more generally to an IC law concerned with alleged executive branch wrongdoing. The old IC statute specified unusual “triggers” for the AG determinations of potential violations of the law that could lead to a court-appointed IC. These were vague and included restrictions on the evidence that the AG could develop or consider. The AG was also generally barred from considering the “state of mind” of a potential target in making the required determinations of potential misconduct. These and other features proved troubling to the Court, but the statute under consideration was directed toward investigations of high-ranking executive branch officials and those who held senior positions in the president’s campaign organization.

The potential reform discussed here would address the very different questions and problems presented by the executive’s use of weaponized law enforcement against Congress. A reform directed toward constraining the executive in prosecuting members of Congress should be written to require, without vague or complex “triggers,” the attorney general’s application to the court for a special counsel. The status of the subject of the investigation—a member of Congress—would be the sole and sufficient trigger for the appointment.

Conclusion: Paths of Reform

The aggressively weaponizing executive pursuing the criminal prosecution of his congressional opposition is something new and deeply consequential. In constructing a reform, Congress may have more constitutional room to maneuver than many may believe after Trump v. United States. The language that the Court there adopted may seem forbidding, with references to Scalia’s dissent in Morrison about the “[I]nvestigation and prosecution of crimes [as] a quintessentially executive function.” But the Court was not confronting in that case the application of those principles to the weaponization of the law against the Congress.

Moreover, it is relevant that much of the “IC laws are gone forever” line of argument neglects that much of the eulogy for the old rests on how unworkable it was—and the tributes to Justice Scalia’s famous dissent were often based on his prophecies about how the law would misfire. He was concerned with the IC law as inviting, among other problems, partisan weaponization, the way in which, as he assessed the case before him, “Congress [had] effectively compelled” investigations of a senior executive branch official.

To the contrary, the reform offered up in this post would seek to answer weaponization in one virulent form it has assumed today. And for all his prescience, the late justice’s vision into the future was somewhat cloudy. He argued that it was an “advantage of the unitary Executive that it can achieve a uniform application of the law.” He did not foresee the arrival of the unitary, weaponizing executive.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article mistakenly indicated that the administration attempted to indict five members of Congress, rather than six. This error has been corrected.