Quick Thoughts on the Tariff Decision and the President's Angry Reaction

A massive defeat for the president and an extraordinary affirmation of the Supreme Court's power.

Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup—brief daily summaries of news developments and commentary related to executive power.

This morning’s tariff decision is a blockbuster on many levels, with implications for the Major Questions Doctrine (MQD) and other statutory interpretation principles and a host of issues cutting across Foreign Relations Law, not to mention U.S. tariff policy and the Trump administration’s foreign policy more generally. What follows are a few quick non-comprehensive thoughts, first about the details of the various opinions, then about bigger-picture doctrinal implications, and finally about the President’s angry reaction to the decision.

How the Court Reasoned

1. The Court ruled 6-3 that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) did not authorize the president to impose tariffs—not just the ones Trump imposed, but any tariffs.

2. There were many opinions, but the controlling one, written by the Chief Justice in part II-B, was joined by Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, Barrett, and Jackson. It reasoned that IEEPA’s authorization to the president to “regulate . . . importation” did not include the power to tax, which is how the Court treated the tariffs. It reached this conclusion through several interpretive inferences. The term “regulate” is not usually meant to include taxation; Congress in its statutes tends to treat regulation and taxation separately; none of the nine things Congress authorized the president to do in the relevant section of IEEPA involved the power to raise revenue; and no president has ever relied on IEEPA to raise revenue. On this last point, the Court discounted the relevance of a lower court decision that had interpreted the identical IEEPA language in the earlier Trading with the Enemy Act to include tariffs. While Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson believed that this section of the opinion (II-B) was enough to resolve the statutory issues in the case, it is not clear to me that the Chief Justice, who wrote this section, thought so. He seemed to connect the statutory analysis in II-B to his prior analysis of the MQD in II-A-2, which garnered only three votes.

3. The majority opinion did not rely on the MQD and the Court significantly splintered on its relevance.

The Chief Justice, in an opinion joined by Justices Gorsuch and Barrett, ruled that the MQD applied to the interpretation of IEEPA and that the president could not “point to clear congressional authorization to justify his extraordinary assertion of the power to impose tariffs.” (internal quotes eliminated).

Justice Kagan, in an opinion joined by Justices Sotomayor and Jackson, explained that she need not rely on the MQD because ordinary statutory interpretation principles alone ruled out the president’s tariffs. Along the way, she repeated her past criticisms of the MQD.

Justice Gorsuch filed a 46-page concurring disquisition on the MQD that took issue with several other justices’ view of the doctrine. He engaged and disagreed with Justice Kagan’s assessment of it. He defended his substantive canon view of the doctrine and disagreed with Justice Barrett’s “commonsense principles of communication” view of it. This disagreement came despite the fact that he and Justice Barrett (and no other justice) joined the Chief Justice’s opinion on the MQD.

Justice Barrett, in her concurring opinion, defended her view of the MQD and disagreed with Justice Gorsuch.

Justice Kavanaugh had a lot to say in his principal dissent, but on the MQD his main point was that it does not apply in the national security or foreign policy context implicated by this case.

4. Justice Jackson wrote a lone concurring opinion to emphasize the importance of legislative history in the statutory interpretation analysis. Justice Thomas wrote a lone dissenting opinion that was a paean to broad executive power. Justices Alito and Sotomayor did not write.

The Bigger Legal Picture

1. The Court did not address the question of what the remedy or remedies, if any, might be for firms that paid tariffs now deemed invalid. This is obviously a massively consequential issue. Justice Kavanaugh in his dissent briefly alluded to the issue but did not speculate on precisely what should happen. The Court made a self-conscious effort not to tip its hand on this issue, which will be addressed in the first instance by courts below. President Trump was probably right when he said at his press conference of this issue: “We'll end up being in court for the next five years.”

2. The doctrinal underpinnings and scope of the MQD in one sense emerged from this decision more confused than ever. Three conservative justices who have been drawn to the doctrine, Justices Gorsuch, Barrett, and Kavanaugh, had sharp disagreements about how it should operate here. The deeper one gets into the weeds of the doctrine, the harder it gets to apply. But need one get into those weeds? The Chief Justice, who has never concerned himself with a theoretical or academic account of the doctrine, had no trouble applying it in a way that gathered the support of Justices Barrett and Gorsuch, even though they disagreed among themselves about the nature of the doctrine.

3. A very significant aspect of the Chief Justice’s MQD analysis is that three conservative justices embraced it to rule against President Trump’s signature policy. And they did so in the most difficult possible context, with an issue involving national security and foreign affairs. This is a rebuttal to those who have claimed that the Court, or at least those three justices, invoke the doctrine opportunistically and politically to hurt Democratic presidents. And I think it signals more clearly than ever that, going forward, this Court is going to view broad delegations of statutory authority to a president to act, and/or extravagant presidential interpretations of authorizations to act, with skepticism. The three justices firmly committed here to the MQD can (if they wish) ensure that outcome in a case of just about any political configuration.

To the extent this is true, it is a hugely important complement to the Court’s emerging broad view of the unitary executive. Put another way, it is a vindication of Sarah Isgur’s view that the tradeoff on the Court for enhancing vertical unitary presidential control is “for the court to rein in Congress’s bad habit of delegating vast and vague powers to the executive branch,” including through MQD. It also puts in a better light the Court’s interim orders to date in Trump 2.0, a large number of which, due to the application strategy of the Solicitor General, involved issues of vertical control. The tariff opinion gives the lie to the notion that the Court is in the bag for the president and also makes its approach to issues of presidential power in Trump 2.0 both clearer and more nuanced.

4. There is a large open question after this opinion about how the MQD applies in so-called national security or foreign affairs cases. I have written about this issue a lot, including in an article with Curt Bradley that was cited in both the Gorsuch and Kavanaugh opinions—opinions that had sharp disagreements on MQD on just this point! Here is what I think preliminarily. Three justices—the Chief Justice and Justices Gorsuch and Barrett—seem ready to apply the MQD in the national security and foreign affairs context without much if any qualification. Three justices—Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson—don’t much care for the MQD in any context. And three justices—Justice Kavanaugh, Thomas, and Alito—appear ready to carve out in this context room for the MQD’s applications. The net impact going forward in this context is hard to fathom, especially if one tries to take the Marks rule seriously. I think Justice Kavanaugh is probably right that “the question of whether or how the major questions doctrine applies in foreign affairs cases remains at least an open question.”

President Trump’s Reaction

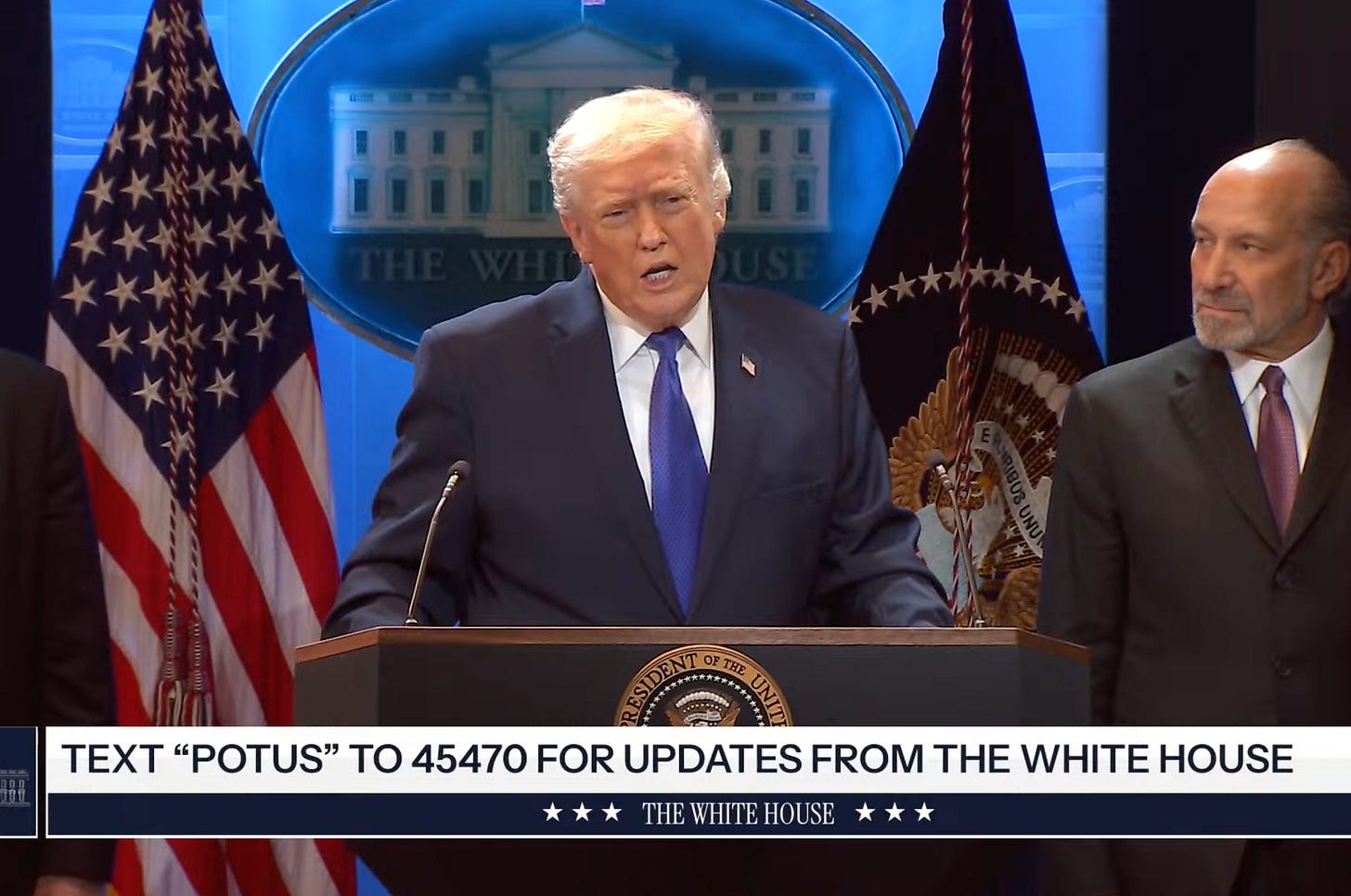

A clearly shaken and angry President Trump gave a press conference following the decision. Up until this point in his second term, he has praised and supported the Court (in contrast to his attitude toward lower courts). But not today. He called justices in the majority, which includes two of his nominees (Justices Gorsuch and Barrett), “politically correct,” “fools and lapdogs for the RINOs and the radical left Democrats,” “unpatriotic and disloyal to our Constitution,” “swayed by foreign interests,” and “afraid,” adding that he was “ashamed” of them “for not having the courage to do what’s right for our country.” He also said the Court’s liberal justices are a “disgrace to our nation” and criticized Justices Gorsuch and Barrett, calling the decision “an embarrassment to their families.”

Trump praised the three dissenters and quoted from Justice Kavanaugh’s dissent:

Although I firmly disagree with the Court’s holding today, the decision might not substantially constrain a President’s ability to order tariffs going forward. That is because numerous other federal statutes authorize the President to impose tariffs and might justify most (if not all) of the tariffs at issue in this case—albeit perhaps with a few additional procedural steps that IEEPA, as an emergency statute, does not require. Those statutes include, for example, the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (Section 232); the Trade Act of 1974 (Sections 122, 201, and 301); and the Tariff Act of 1930 (Section 338). In essence, the Court today concludes that the President checked the wrong statutory box by relying on IEEPA rather than another statute to impose these tariffs.

Yes, the president has many other statutory bases for imposing tariffs. But there is a reason why Trump relied on IEEPA and not these other statutes. As a general matter, the other statutes require more than just “a few additional procedural steps.” They require, in places, investigations and, in places, significant findings; and the scope of the tariffs they authorize is limited in various ways. Invocation of these other authorities requires more than box checking. They require serious work by competent officials in the government and they are constrained in various ways by factual realities and legal limits.

The thrust of Trump’s press conference was that he would rely on these alternative authorities and would be able to do everything he did under the IEEPA tariffs, if not more, though he acknowledged, with understatement, that it might be a “little more complicated” and “the process takes a little time.” I doubt that these alternate authorities, even with time, will be full tariff substitutes for the IEEPA tariffs, but there are many statutory tools Trump might use beyond tariffs. Indeed, Trump suggested at the press conference that he could and might rely on other elements of IEEPA to bring greater pain to foreign countries than a tariff, including cutting off a country’s business in the United States altogether.

It is too hard now to assess all of these complications or the implications for the various new trade deals now in place. But two larger points emerged from the press conference.

First, Congress has indeed given the president many other statutory foreign policy tools that the president can use as economic sticks to continue to coerce countries to meet his economic demands. The fight will now shift from IEEPA to these other statutes (or to different aspects of IEEPA). If the administration takes the proper time and does all of the work needed under these statutes—a very, very big if—it can continue to assert significant economic pressure on foreign countries. The courts will have the final say on the legality of what the president does under these alternative authorities, but the president (again, with proper advanced lawyering) will have the upper hand.

Second, the Trump press conference was an amazing portrait of a president who claims to be unbound by law seethingly acquiescing in a court ruling on “an important case to me” that he abhorred with every fiber of his body. It is clear the administration will use every alternative legal tool at its disposal to replicate or go further in deploying international economic weapons. That is its legal prerogative. But still, Trump’s anger combined with his acquiescence in the ruling elevated the Court and was a remarkable testament to its power.

Thanks to Tia Sewell for editorial assistance