Presidential Pretext and the Supreme Court

How much will the actual reasons for the Cook firing matter?

Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup—brief daily summaries of news developments and commentary related to executive power.

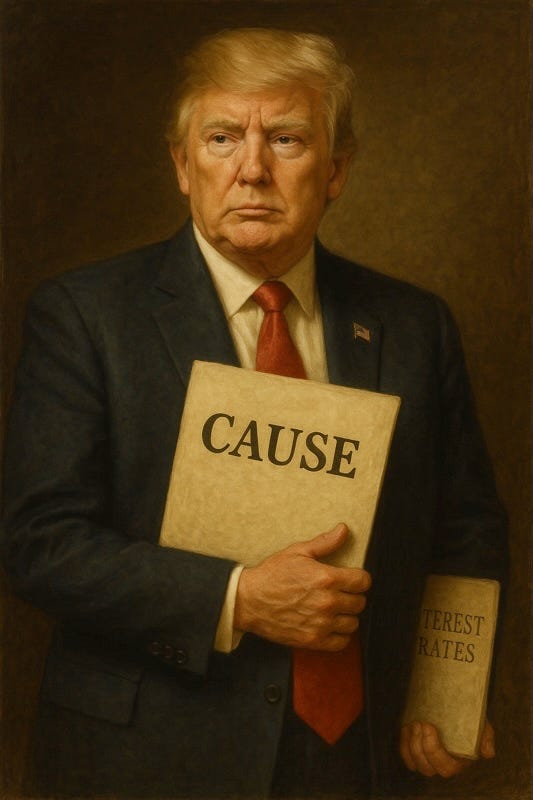

In the case of President Trump’s firing of Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook, the Supreme Court will confront a hard choice: resolve legal issues at a high level of abstraction, formalistically, or find a way to take into account what the case is really about. On the formal level, it could stringently apply standard tools of legal interpretation in deciding whether the president has unreviewable discretion, or something less, in determining “cause” to fire a Fed official. Or it could weigh in its decision the evident facts of the matter, which is that the president seeks to control monetary policy and has weaponized the cause requirement to develop a pretextual “firing offense.”

Adopting the second of these approaches requires some consideration of evidence of motive or purpose. The government, supported by the dissent in the appellate decision, argues that “normally,” the courts will not look into motive. This is not the normal case. The question is whether and how the Court will respond to its abnormality.

There is little dispute about the administration’s larger purposes in the Cook firing—even if it is also given the benefit of great doubt and credited with some concern about the issue of mortgage fraud. Trump has been quite unhappy that the Fed would not cut interest rates when and to the extent he wanted. This led to the first of his suggestions that Fed officials who stood in his way might have given him cause for firing. He aired an allegation of potential “fraud” against Chairman Powell, in connection with the renovation of Fed facilities, but relented under market pressures. Cook was next to be accused of fraud, and this time the head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Bill Pulte, made a public show of the accusation when he published on social media a referral to the Department of Justice. The government had put its weaponization strategies and capacities to work in making the claim of fraud in Cook’s case, and the basis for “cause,” it could not successfully develop in Powell’s. (Meanwhile, Pulte, who had also developed a mortgage fraud claim against another Trump adversary, New York State Attorney General Letitia James, successfully pushed with controversial Justice Department official Ed Martin to force out the Trump-appointed U.S. attorney who was poised to drop the case for lack of merit. This development added to justified doubts about Pulte’s purposes in building cases like Cook’s and James’).

In a remarkable move that underscores what “is going on,” the president has since advanced, and the Senate confirmed, a new appointment to the Fed Board of Governors, Stephen Miran, with the unprecedented understanding that Miran would assume the position only on leave from his White House staff position on the Council of Economic Advisers. Trump’s wider purpose made plain in all three cases—the attack on Powell, the firing of Cook, and the appointment of Miran—was to bring the Fed under his direct control.

The government has proceeded to argue for Trump’s unreviewable discretion to fire Cook in a way that ensures that pretextual firings for cause could become available to future presidents as a matter of course.

It has had to adjust its argument to the Court’s indication that, for purposes of the president’s removal authority, the Fed may be more independent than other agencies, because it is “a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second banks of the United States.” So the administration has (for now) declined to frontally challenge the constitutionality of the statutory “cause” requirement and instead contends that it has complied with it.

But what would compliance entail? The government defines “cause” to preclude only dismissal for policy agreements—such as disagreements over interest rates—or simply because the president would prefer his own pick for one of the seats. But, the government argues, as did the dissent in the Court of Appeals, that any reason given need simply refer summarily to a president’s concern with the official’s “conduct, ability, fitness, or competence.” Provided that the president does not state policy disagreement as the reason for a firing or simply declares a preference for another to hold the position, any reason given for cause to question “conduct, ability, fitness, or competence” is sufficient—that is, not subject to judicial review.

To sum it up: What the president says goes. He can assert a deficiency with or without a basis, disingenuously or in good faith. He can just say it, and that ends the matter. And it is at this point that the government lays down its constitutional marker. “Any scrutiny” beyond these baseline requirements would infringe dangerously on the president’s Article II authority.

As I have written previously, this position incentivizes a weaponizing government with vast power at its disposal to develop a claim of whatever merit or seriousness that supplies the “cause.” But the weaponization of power to supply a criminal charge against the official does not exhaust the options available to a government on the hunt for cause.

First, it bears noting that this firing for cause based on asserted issues of “conduct, ability, fitness, or competence” need not concern only the official’s own conduct. For example, suppose that ten years earlier a business in which the official was a principle or major investor failed to pay taxes owed or ran afoul of relevant regulations. While the delinquency was not the official’s, a president could cite the questionable associations as undercutting his, or the public’s confidence, in the official’s fitness to serve in a high public office. This comes up all the time in executive and legislative branch “vetting” of officials being prepared for potential nomination. They are called to answer for any background issues, even if the connections to misconduct can be one or two steps removed form evidence of individual wrongdoing. Problematic associations can implicate questionable judgment, and so forth.

Second, not all the asserted causes for dismissal would have to rest on opposition research into misconduct in the present or years past. Imagine a Fed governor who delivers a speech on the role of the Fed, the reasons for its decisions, and recent votes. The president can disavow that his concern is with the policy expressed and argue that the governor went too far in explaining the Fed’s inner deliberations, or misrepresented the facts about the economy, or distorted the effects of the decision to raise or not raise the rates, or the level to which they were raised. He or she was misleading the public on grave matters and has lost the president’s confidence. Or the views expressed in the speech suggest that he or she subscribes to a “radical left” agenda for country that cannot be reconciled with the high duties of the office.

On the government’s theory, the rejoinder that the president was evidently motivated by policy disagreement, and that he merely wished to replace the official with one more favorable to his policy views, must fail. For the president, in these hypotheticals, did not give those reasons for the firing; he gave another, and once he meets that baseline requirement, an examination into his true intentions—an inquiry into motive—would be impermissible. Yet, as in the Cook case, the motive on the public record might point to an orchestrated claim of fraud for the very purposes of replacing this official with another of the president’s choosing who will reliably support the president’s policy objectives.

On the government’s reading of cause, there little of substance left of it, none that could achieve the purpose of construing “cause” in a fashion that insulates the Fed from political pressure. The limitation to “cause” is stripped down to a largely performative function. This is the heart of the matter before the Court. Unfortunately, the point can be lost in this case which also features the argument, persuasive to the Court of Appeals, that Cook has a property interest in the position and is therefore entitled to a notice and hearing before she is ousted from it. The cause requirement is best, and in my view, more correctly seen as serving a key public policy interest—insulating the Fed from political pressure—and less if at all any personal property interest on the part of the Fed governor.

The government’s theory of the case undermines this key interest to the point of rendering it a nullity. One could say, fairly, that the unreviewable discretion the judge and the government argue for simply invites the application of political pressure, in this instance an all-out presidential initiative to seize control over the Fed.

The government rests its insistence that “any” inquiry is impermissible on Trump v. Hawaii, one of the “travel ban” cases decided in Trump 1.0, and on Trump v. United States, the presidential immunity decision. Neither is apposite.

In the travel ban case, the Court emphasized that it was addressing a matter “within the core of executive authority,” namely that “the admission of exclusion of foreign nationals” is a “‘fundamental sovereign attribute exercised by the Government’s political departments, largely immune from judicial control [citation omitted].” The “overlap” of immigration authority with national security meant that “our inquiry to matters of entry and national security is highly constrained.” Similarly, in the immunity case, allegations of “improper purpose do not divest the President of exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials.” Moreover, the opening up inquiry into motive would not be subject to any limiting principle, such it would “risk exposing even the most obvious instances of official conduct to judicial examination on the mere allegation of improper purpose…”

The distinction between these cases and Cook’s seems clear. In Cook, the administration has set aside any claim of absolute constitutional power-to-fire under Article II and is arguing instead over the extent to which the statutory “for cause” requirement limits the presidents in dismissing a Fed official. Where the government has acknowledged that the president must give a reason, and that any such justification cannot be a policy disagreement or simple wish to replace one official with another, the record the president establishes for that reason seems appropriately subject to review.

It is notable that the government’s petition to the Court adds to the record of pretext in the Cook firing. The Solicitor General denies that Cook was entitled to notice and the opportunity to respond but, to be on the safe side, insists that she received both. He advises the Court that the “President notified Cook of the charges against her and waited five days for her to respond before removing her.” Then the government defines “notifying Cook” to mean that she received word of the criminal referral when Pulte posted it to the word. When, five days later, Trump called on her to resign, she issued a statement that he would not resign but also affirmed that she did “intend to take any questions about [her] financial history seriously as a member of the Federal Reserve and so [she is] gathering the accurate information to answer any legitimate questions and provide the facts.”

The Government makes no mention of this commitment, and the administration ignored it at the time. The next day, U.S. Pardon Attorney Ed Martin, who is also (more than a little ironically) Director of DOJ’s Weaponization Working Group, called on Fed Chair Powell to fire Cook. The day after that, Trump told reporters that he would fire her if she did not resign. Three days later, he notified Cook by letter that he was removing her from her position, effective immediately. There is not, then, much support for the government’s picture to the Court of a president “waiting” for Cook’s side of the story. The point here is not whether or not Cook was entitled to notice and an opportunity to respond, but that the government’s insistence that Trump intended to provide either, but was left “waiting,” cannot be taken seriously.

Inquiry into presidential motive is delicate business, to be sure. But the cases cited by the government arguing against “any” such inquiry hardly settle the matter. In what the Court has characterized as “unusual circumstances,” it has been willing to closely examine the record where there is clear evidence of pretextual executive branch decision-making. In the case involving the Secretary of Commerce’s inclusion of a citizenship question in the census questionnaire, the Court rejected the government’s “contrived” rationale for this action—that it was seeking citizenship information to better enforce the Voting Rights Act. The Court could not “ignore the disconnect between the decision made and the explanation given.” The explanation given could have justified the decision, but it was not, in fact, the true purpose behind adding the citizenship question. The record indicated a “mismatch between the decision the Secretary made and the rationale he provided.” The Court proceeded to consider the actual reasons for the Government’s action if “judicial review is to be more than an empty ritual….”

The Fed case also arises in “unusual circumstances.” The Court has signaled that there are “unique” features of this agency that may distinguish it from others on the question of the president’s constitutional removal authority. The case is now one of statutory interpretation, and the stakes are high precisely because of these “unique” features of the Fed and its role. Engaging with the pretextual nature of the claims behind the dismissal of Fed Governor Cook is necessary to judicial review “if [it] is to be more than an empty ritual.”