Edward Levi’s Department of Justice

What a Difference a Half Century Makes

Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup—brief daily summaries of news developments and commentary related to executive power.

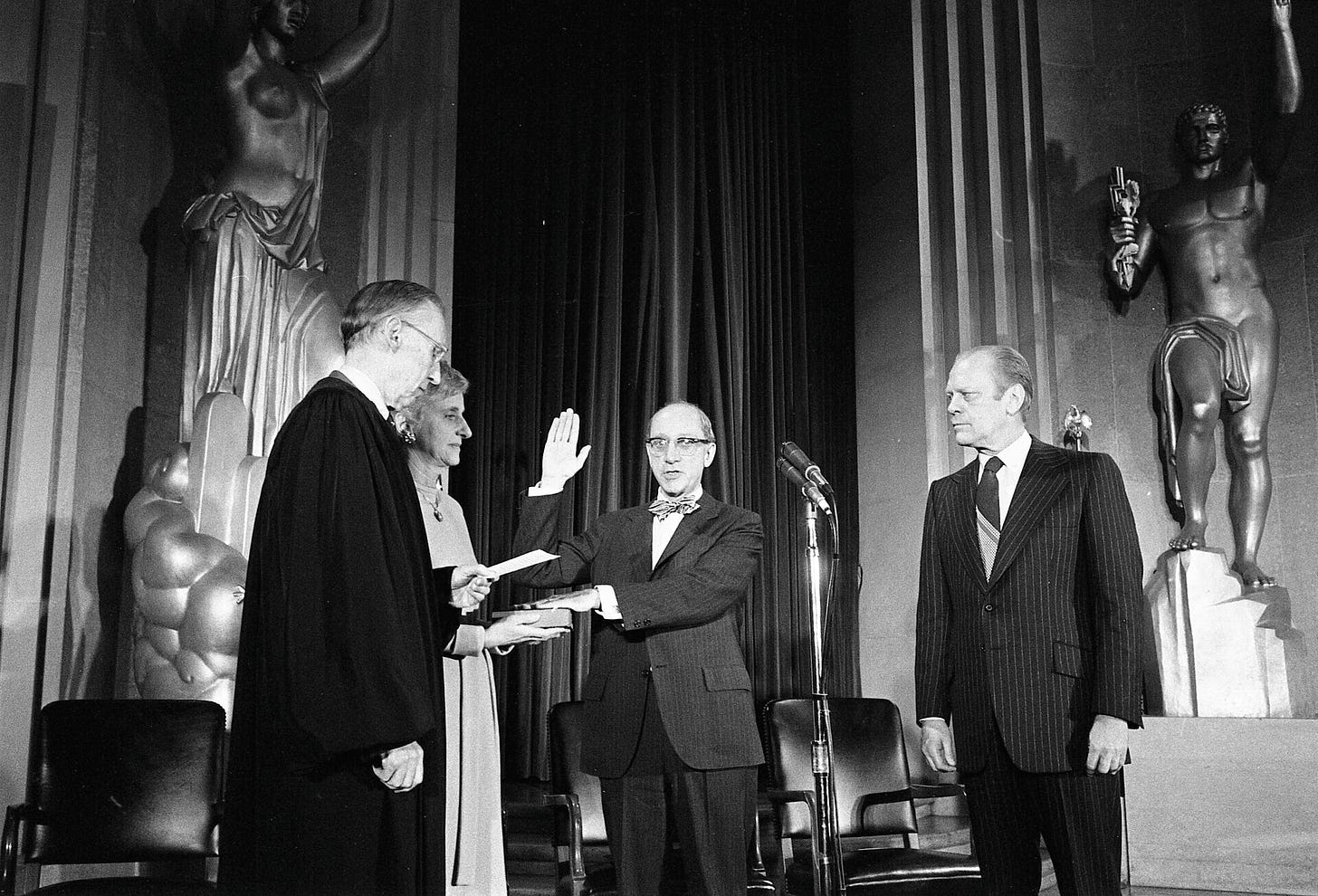

Fifty-one years ago today, President Gerald Ford formally nominated Edward H. Levi to be attorney general. Three weeks later, after a swift Senate confirmation hearing, and with President Gerald Ford looking on, Justice Lewis Powell swore in Levi in the Department of Justice’s Great Hall.

It was a low point for the department. Watergate had driven Richard Nixon from office six months earlier and had exposed a lawless White House. The department’s reputation had been badly damaged by the criminal convictions of two of Levi’s predecessors, John Mitchell and Richard Kleindienst, many high-profile disclosures of executive branch abuses of power, and shocking congressional and media revelations about intelligence and law-enforcement misconduct. The department was demoralized and public trust in it had collapsed.

Levi was “a genuine intellectual, a gifted scholar and teacher, a former law school dean and university president, and an accomplished administrator of unimpeachable integrity who had experience in the Department of Justice but who had never been involved in politics,” as Larry Kramer said in a preface to a collection of Levi’s speeches. At the swearing-in ceremony President Ford described Levi as “a person who will make certain that all of our fellow citizens believe this government when laws are interpreted, when laws are carried out. And this faith is vitally important for our country at this very troubled time.”

Amazingly, Levi succeeded in this task. He did so by his example—he was invariably honest, candid, pragmatic, intelligent, informed, and as non-ideological as one could be. He also instituted or shepherded a number of vital reforms—the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (which Congress enacted after his tenure), the Attorney General Guidelines governing FBI domestic security investigations, the first versions of what would become the policy of limiting White House contacts with DOJ, and much more. These and related reforms were at the foundation of decades of relatively stable norms of non-politicized law enforcement—with an important exception noted below.

Levi was able to pull off the appearance and reality of impartial law enforcement even while making tough law enforcement calls. As he said after nearly two years in office:

Much of what the administration of justice represents has to be seen and read from its formal actions. I have assumed the most important aspect was to try to make pervasive a certain sense of fairness and responsibility—and adherence to the law—and a clear denial of partisan political use, and this with a willingness to try to confront more squarely the law’s proper role in certain controversial areas. I knew the second might defeat the first, but I thought both were necessary. Fairness and responsibility, which may sound bland and easy, but are not, after all assume a proper use of the instrument, and law has a part to play in clarifying and helping to maintain the values involved in the solution of many problems.

Levi made difficult law enforcement calls, not just, for example, in areas like pornography and busing, but also in declining to reopen or expand Watergate prosecutions and in resisting prosecutions for pre-1975 intelligence abuses.

These latter decisions, I think, aimed in part to defeat what Levi perceived as a danger of tit for tat in law enforcement. As he said in February 1976:

Popular governments are prone to cycles. It is one of their strengths as well as their weaknesses. In the confused days between the end of the Revolutionary War and the Constitutional Convention George Washington wrote, “We are apt to run from one extreme to another.” The Constitution was intended to form a government which recognized, moderated, but did not entirely do away with this tendency. We are in such a period of cyclical reaction today, justifying what we do now as a kind of getting even with the events of prior years. This in itself is another form of the game of victims and losers. We are adversaries not only with ourselves, but also with the past.

Levi would be appalled by the extent to which the department is now being used for “getting even with the events of prior years.”

Modern DOJ weaponization did not start with Donald Trump. It began, I think, with the 1978 Independent Counsel statute that sought to depoliticize law enforcement functions but ended up badly exacerbating DOJ politicization. Levi strongly opposed the Independent Counsel statute and with two other former attorneys general filed an amicus brief in Morrison v. Olson, with David Strauss as counsel, that anticipated many of the themes in Justice Scalia’s famous dissent.

Levi gave farewell remarks 49 years ago tomorrow that can still be found on the DOJ website:

When I took the oath of office almost two years ago in this Hall before some of you—among other things I said was the following: “The law is a servant of our society. Its enforcement administration can give more effective meaning to our common goals.”

Among these common goals are: domestic tranquility, the blessings of liberty, the establishment of justice.

These goals do not bring themselves into being. If we are to have a government of laws and not of men, then it takes particularly dedicated men and women to accomplish this through their zeal and determination, and also their concern for fairness and impartiality.

And I know that this Department always has had such dedicated men and women and I recalled then with great pride the time I spent in this Department.

I said we have lived in a time of change and corrosive skepticism and cynicism concerning the administration of justice. Nothing can more weaken the quality of life or more imperil the realization of the goals we all hold dear than our failure to make clear by words and deed that our law is not an instrument of partisan purpose, and it is not to be used in ways which are careless of the higher values which are within all of us. . . .

I want now to say thank you for the dedicated service which you have always given and are now giving. I leave confident that the morale and purpose of this Department are high. We have shown that the administration of justice can be fair, can be effective, can be non-partisan.

These are goals which can never be won for all time. They must always be won anew. I know you will be steadfast in your adherence to them.

Levi was entirely justified in claiming that he had transformed the department in these ways. It was a very different time with a very different politics. A half century later, “partisan purpose” and “getting even” have replaced a “concern for fairness and impartiality.” How we got here is a sad story that stretches back decades. How, if ever, we get back to Levi’s Justice Department is hard now to fathom, and I will leave for discussion another day.

I thank Matt Fidel and Tia Sewell for editorial assistance